It is well known that when Elizabeth I died on 24 March 1603 at Richmond Palace, she was succeeded on the throne of England by first cousin twice removed, James VI of Scotland. Although Elizabeth had consented to the execution of James’s mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1587, the mainly cordial relations between the Scottish king and the English queen were undoubtedly influenced by James’s hope that he would eventually be named successor to Elizabeth. The Tudor queen had been notoriously reluctant during her forty-four-year reign to name a successor, but as her life drew to a close Elizabeth realised that the maintenance of peace in her kingdom depended greatly on a stable succession. The peaceful accession of James in the spring of 1603, however, has obscured the dynastic and political relevance of a forgotten noblewoman – Anne Stanley, later Countess of Castlehaven. In the twenty-first century, Anne is generally known not for her dynastic importance but for her testimony against her husband, which led to his execution for sodomy in 1631.

According to Henry VIII’s last will and testament of 1546, which was created a few weeks before his death, Anne Stanley was rightful queen of England upon the death of Elizabeth I. Having nominated his three children – Edward, Mary and Elizabeth – as heirs to the English throne, Henry proceeded to exclude the Scottish branch of the family – the descendants of his elder sister, Margaret, Queen of Scotland – from the line of succession to the Tudor crown. This may have been due essentially to Anglo-Scottish relations in the 1540s, which gradually worsened to the point of no return. Rather than presiding over the betrothal of his son Edward to the infant Mary, Queen of Scots, Henry learned of the Scottish queen’s betrothal to the French dauphin. The cementing of the ‘Auld Alliance’ between Scotland and France confirmed Henry’s decision to exclude his sister Margaret’s descendants from consideration in the line of succession. Instead, he instructed that the English crown should pass to the descendants of his younger sister Mary, dowager queen of France, should his three heirs die without producing children of their own.

According to Henry VIII’s last will and testament of 1546, which was created a few weeks before his death, Anne Stanley was rightful queen of England upon the death of Elizabeth I. Having nominated his three children – Edward, Mary and Elizabeth – as heirs to the English throne, Henry proceeded to exclude the Scottish branch of the family – the descendants of his elder sister, Margaret, Queen of Scotland – from the line of succession to the Tudor crown. This may have been due essentially to Anglo-Scottish relations in the 1540s, which gradually worsened to the point of no return. Rather than presiding over the betrothal of his son Edward to the infant Mary, Queen of Scots, Henry learned of the Scottish queen’s betrothal to the French dauphin. The cementing of the ‘Auld Alliance’ between Scotland and France confirmed Henry’s decision to exclude his sister Margaret’s descendants from consideration in the line of succession. Instead, he instructed that the English crown should pass to the descendants of his younger sister Mary, dowager queen of France, should his three heirs die without producing children of their own.

Edward VI died in July 1553 at the age of fifteen; in the weeks prior to his death he directly ignored his father’s wishes regarding the succession and excluded both of his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, from inheriting the throne. Instead, he named his cousin Lady Jane Grey as heir to the throne. Jane’s regime, however, collapsed within days of the proclamation of her queenship, and Mary Tudor seized the throne with the assistance of considerable popular and military support from her subjects. Mary, who reigned until 1558, was the only one of Henry VIII’s three children to honour his wishes concerning the English succession. When she died, the crown passed to her half-sister Elizabeth. Like Edward VI, Elizabeth was to disregard her father’s last will and testament. The actions of Lady Jane Grey and the Dudley family in 1553 seems to have led Elizabeth to associate the Greys with treason. Her attitude to Jane’s sisters Katherine and Mary was markedly hostile, and when both sisters married without royal permission, they were swiftly placed under house arrest and were never restored to royal favour. Katherine’s marriage to Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, was declared invalid and their two sons were deemed illegitimate. According to Henry VIII’s will, Katherine and her sons were the lawful heirs to Elizabeth’s throne, but the Tudor queen’s belief that the Seymour-Grey marriage was invalid ensured that Katherine’s claim to the throne failed to materialise. The youngest Grey sister, Mary, does not appear to have been regarded either by the queen and her councillors or by the wider realm as a viable successor to the throne.

By 1578, when Mary Grey died, the Elizabethan succession was a highly precarious issue. Firstly, this was because there was no indication that the forty-four-year-old Elizabeth would marry and produce heirs of her own. Secondly, Mary, Queen of Scots, had been compelled to abdicate from her throne in 1567 and had sought refuge in England shortly afterwards, but both Elizabeth and her government were unreceptive to the prospect of Mary becoming Queen of England. Elizabeth’s councillors became more hostile to Mary when the papal bull of 1570 was issued, explicitly inviting Elizabeth’s assassination and the restoration of Roman Catholicism. Henry VIII’s will, moreover, had openly forbidden Mary, Queen of Scots’ accession to the English throne. The exclusion of the Scottish line, therefore, left Elizabeth with few options, and it is perhaps unsurprising that her attitude to the succession was, at best, ambivalent. The execution of Lady Jane Grey in 1554 and the deaths of her sisters Katherine and Mary in 1568 and 1578, respectively, meant that Elizabeth’s heir was Margaret Stanley, Countess of Derby, a grandniece of Henry VIII.

Ferdinando Stanley

It is questionable, however, whether Elizabeth ever seriously considered Margaret as a plausible successor. The rumoured Catholic sympathies of Margaret’s husband were unwelcome, especially in an environment of worsening conditions for English Catholics in the 1570s. Margaret’s ambition and recklessness, however, definitively excluded her from the line of succession when she was placed under house arrest for allegedly using sorcery to predict the date of Elizabeth’s death. The countess was never restored to royal favour, and died in 1596. Her eldest son Ferdinando had died in 1594, which meant that Margaret was replaced at her death by her granddaughter, Ferdinando’s daughter Anne Stanley, as heiress presumptive. Anne’s dynastic status was arguably bolstered by the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots in 1587, which removed the most plausible candidate – at least from the perspective of the Catholic powers in Europe – from the line of succession to the English throne.

Henry VIII’s will stipulated that Elizabeth would be succeeded on her death by the descendants of Mary Tudor, represented in 1596 by Anne Stanley. Elizabeth, however, ignored her father’s wishes and instead selected James VI of Scotland, son of Mary, Queen of Scots, as her heir. If Henry’s wishes had been respected, then the twenty-two-year-old Anne would have been crowned Queen of England in the spring of 1603. The smoothness of the Stuart transition to power, however, has obscured Anne’s dynastic and political importance, and she remains largely forgotten today. Her claim to fame rests largely on the scandal that enveloped her second husband.

In 1607, four years after James VI’s accession to the English throne, Anne married Gray Brydges, Baron Chandos of Sudeley Castle. Gray and Anne appear to have lived in luxury; the baron was described as ‘king of the Cotswolds’. Anne, however, was said to be a spendthrift. The baron died in 1621 and Anne was left a widow with four young children and an income of £800 a year. Three years later, at the age of forty-four, Anne married Mervyn Touchet, Earl of Castlehaven. As Cynthia Herrup has noted, regardless of the nature of the relationship between Mervyn and Anne, ‘together they could claim ancient lineage, extensive property, and court connections.’ The couple lived mainly at Fonthill Gifford in Wiltshire after their wedding, but their married life does not appear to have been happy. According to the earl’s son, Lord Audley, Anne was promiscuous and took several of her servants as lovers. The earl was also rumoured to be intending his son’s disinheritance, and Lord Audley was further incensed when Castlehaven encouraged Audley’s wife to have sexual relations with the earl’s servant Henry Skipwith. It later emerged that Castlehaven had sanctioned his wife’s rape at the hands of a servant, and it was also alleged that the earl had had sexual relations with both male and female members of staff, including with his footman Lawrence Fitzpatrick. Anne testified that she had been raped and had made a suicide attempt.

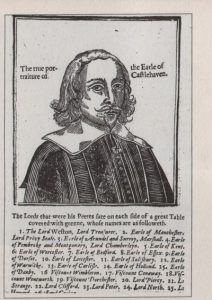

The Earl of Castlehaven

In the spring of 1631, Castlehaven was charged with sodomy and the rape of his wife. Giles Broadway was also charged with raping the countess, while Fitzpatrick was charged with sodomy. Castlehaven, clearly, was unable to manage his household effectively – a damning failure according to the standards of early modern England. The earl denied the charges and slandered his wife as a wh*re and a liar. Castlehaven was nonetheless beheaded on 14 May; Broadway and Fitzpatrick were hanged in July. On the scaffold, Anne’s rapist Broadway accused her of being a wicked woman and of having murdered her own child: ‘the wickedest woman in the world’. The countess was later required to seek a pardon from the crown for her ‘sexual immorality and debauchery’. She died in October 1647 at the age of sixty-seven.

Anne Stanley has been neglected in both academic and popular studies of Tudor history, especially in regards to the controversial issue of the Elizabethan succession. While she herself does not appear to have made an active claim to the throne, she was, according to Henry VIII’s last will and testament of 1546, the rightful queen of England in 1603.

What do you think? Please do share your views as a comment below.

Conor Byrne studied at the universities of Exeter and York. He specialises in late medieval and early modern English history, with an emphasis on royal history, gender relations and Tudor queenship. His first book, Katherine Howard: A New History (2014) was published by MadeGlobal and has been described as ‘a brilliant study’, ‘a new and refreshing biography of Katherine Howard’ and ‘a timely addition to Tudor scholarship’. Conor’s second book Queenship in England (2017) was also published by MadeGlobal and provides an in-depth analysis of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century queenship. He runs an active Facebook page at www.facebook.com/ConorByrneHistorian.

Elizabeth probably may not have named a successor on her death bed (this my be a story put forward by Robert Cecil, her chief minister), but she had certainly indicated for the previous two decades or so that James of Scotland would be her successor. James was the only serious male candidate and that was what counted after decades of female rule, not Henry VIII’s dusty will. James was widely accepted by English politicians from well before the time of his mother’s execution. This execution would remove a major obstacle to James’ accession, as the Earl of Leicester explained to the Scottish ambassador. On the other hand, there seems to be no indication that it ever occurred to Elizabethans that Anne Stanley should inherit the throne. There was a little support for Arabella Stuart, but then her grandmothers had championed her cause for decades; some Catholics wanted Philip II’s daughter Isabella. But these were ladies, also, and apparently nobody thought of Anne Stanley.

The succession after the Grey sisters were one by one excluded or died, despite Katherine having two sons, should have moved over to the offspring of Eleanor Brandon, (Clifford by marriage) Countess of Cumberland, thus her daughter, Margaret Stanley and granddaughter, Anne Stanley, who I know very little about so your article is a most welcome introduction. However, political backhanded agreements were made which indicated that James was certainly the favourite candidate to succeed. He was male, mature, but still young, he had a young family already, he was the right religious faith, he seemed sensible and was well educated and he was a candidate who at least the right political people wanted for peace and stability. Elizabeth may not have named him, but she gave him a pension, she kept good relations with him and some kind of behind the scenes understanding seems to have indicated that James would succeed. The Third Succession Act did make provision for future descendants of Henry Viii to change things and put their own candidate on the throne. The problem with Henry Viii and his will is that he didn’t foresee anyone other than his son going on to have his own sons and if not the two sisters, Mary and Elizabeth would succeed and have children. I doubt he really envisaged anyone else but a full Tudor on the throne. His removal of the Scottish line was of course made at a time of active conflict and by now things had calmed down with the two noisy neighbours of England and Scotland. There is also the possibility that the exclusion didn’t include Lady Margaret Douglas, whose son, Lord Henry Darnley married his cousin, Mary Queen of Scots and gave both her and any children an increasingly good claim to the English crown. Elizabeth had partly given the nod to Mary’s claim when things were good in the early days of her own reign and although things changed, James was now seeing himself as the fulfilment of that nod. Robert Cecil worked behind the scenes to secure the English crown in exchange for advancement and promises on behalf of James and was one of those who promoted the idea of his succession in England. There were a number of candidates who could have pressed a claim, but many had died out by the end of the century. I believe there is some evidence to support an agreement within the Council to make sure James had a smooth transition and persuaded Elizabeth to agree at the end of her life, but I also believe it was an unspoken truth for some years that James would become King. It was a pity that the natural and legal succession didn’t pass from one to another, with the next heir named in the late King Henry’s will taking over, as with this lady for example, because it would be interesting to see the outcome. Perhaps the obsession with witches might and bloody civil war might have been avoided. English Catholics put their faith in James also, only to be betrayed and sold out in favour of a treaty with Spain, who also betrayed them and they lost patience, were told to leave the country or conform and thus the Gunpowder Plot followed. James also gave all the Government positions to Scots which annoyed his new English gentlemen and Court and this was also resented by his subjects and was an element in the above Plot. Cstesby said he would blow “,this Scottish devil back to the bogs and heather from wench he came” . An English Lady may possibly have been more acceptable to some elements, but a male was seen as a way to bring back security and peace.

I think it’s better the way things went. Afterall also the Scottish Royalties had their rights ….. and personally what matters.if one worships our Lord using Anglican (Church of England) or Catholic worship as long as the Church keeps well away from Political Decisions of the Country….

In an ideal world I would agree, but the two are linked because they both affect personal and social needs, life and almost everything else. The problem back then was the way both were used by the leaders of every country in order to quash the freedom of those individuals. The same conditions don’t apply today because we don’t have a Monarchy that thinks it is divine and our Parliament is legally and morally answerable to the people, even if it often forgets that. It is also debatable because many social issues, like homelessness, concern for the poor and hungry and justice are concepts shared by many people of many different faiths. If the Church sees a Government acting to make the life of the weakest members of society, the old, the vulnerable, the poor, disabled, prisoners, refugees, it can be argued they have a duty to speak out and that laws to improve things be encouraged by Christian and other religious people in Parliament. Where the political agenda of the past pushed the boundaries was that it used one faith to persecute another and the social order was based not on working for a fair society, but on the King and State Church, supported by a nobility make all the rules and everyone else obeys. By the sixteenth century this concept of a society were everything and everyone had their place was being challenged and attempts made to bring new ideas in to change this. Several protests and economic and religious rebellions highlighted the fact that the King was indeed fallible and everything was not just. People began to read more and express their ideas, even found support in the Bible for their cause. By the 1640s, all of this was ripe for the explosion which followed. It took another two hundred years for the first social changes to begin, but after the English Civil War a King had to take notice of the people.

James, at the end of the day probably was the best candidate all round, but he was soon to realise the value of making a promise, especially if it was broken. He was one of the best educated and genuinely intelligent Kings to sit on the English throne and he was also one of the few to challenge the established religious order and the new groups of none conformity like the Puritans and end up with a stable settlement and a new translation of the Bible as his legacy. He was a man to tried to balance difficult parties but he was also the author of two books which had terrible consequences over the next 150 years for hundreds of his new subjects.

James was called the wisest fool in Christendom and although it is natural that he would appoint a number of Scots to various Government posts, especially if they had shown ability, but his mistake was to place them in a majority in the Court. James was a man of principle but he also knew how to compromise. His other mistake was wanting both the much needed peace with Spain and more stringent laws against Catholics. He should have realised that a bunch of young, restless, unemployed, spoilt, persecuted and privileged men with nothing to do and a lot of anger would have found a way to make their world better, if no redress came from the new King for years of imprisonment, fines, searching their homes, refusal to allow them to practice an ancient faith, even to take part in service of the crown, of hardships caused by fines and now betrayal would push them to the edge. These men were desperate as well as passionate and even fanatical, but James fed that and the Gunpowder Plot resulted. However, he could also find better ways of ordinary justice and his treaty on witchcraft was meant as a guide to who was innocent as well as guilty. He had his judges review major cases in the Star Chamber and could be remarkably fair. Although his son took on his model of kingship his failure was not knowing when compromise was the thing that could have saved his kingship and life and that a King was also subject to the law.

I’m curious about how it was that Anne Stanley should have been prefered for the royal succession over her uncle William Stanley (W.S.). Wouldn’t the second male son of Margaret Stanley have had preference over his niece?

There was a delay of nearly a year in W.S. inheriting his brother Ferdinando’s title and estates of Earl of Derby because Anne’s mother Alice Spencer Stanley was pregnant when Ferdinando suddenly died, and the infant could have been a boy — and thus the new Earl. Even after W.S. inherited the title of Earl, Alice continued to sue for much of Ferdinando’s estates and wealth. A final settlement did not happen until 1610, when Robert Cecil brokered a settlement in favor of his niece Elizabeth Vere Stanley (W.S.’s wife), which by the way included having Elizabeth take on the duties of “Lord of Man” in control of the Isle of Man.

So, if a boy child of Ferdinando’s could have bumped W.S. from inheriting the Earldom, and obviously bumped Anne Stanley from inheriting, how is it that Anne should have had preference over her uncle W.S. for the crown itself?

I’ll alert Conor to your comment, but my understanding of the situation is that Anne became heir presumptive following the death of Margaret Clifford, the previous heir presumptive, because Anne was the daughter of Ferdinando, eldest surviving son of Margaret. William was a younger son of Margaret. It’s like the royal family today. The heir to the throne is Prince Charles and then it passes on to his eldest child and then on to his eldest child and so on, rather than passing on to Prince Henry (Harry). Hope that makes sense, I haven’t had my morning coffee yet!

Thanks, although “eldest male child” might be more accurate in an age where primogeniture ruled the roost. After all, “Bloody” Mary and Elizabeth each had to wait for their younger half-brother to kick the bucket before they could respectively step up to the throne. So, in what way had that been changed in 1603? I recently heard that a year ago Parliament was considering a law which would make female heirs equal to males in line to the throne — which means that regal primogeniture still rules the roost even today!

Margaret Clifford was the only surviving child of Lady Eleanor Brandon and Henry Clifford, hence why she was heir presumptive, and then her son, Ferdinando Stanley, only had daughters, which is why Anne was the heir presumptive. Margaret and Anne didn’t have surviving brothers to be claimants over them. I am certainly not an expert in the laws regarding inheritance though, just sharing my understanding from what I’ve read of these people.

In 2013 the Succession to the Crown Act was passed, replacing the system of male-preference primogeniture that the 1701 Act of Settlement had established. so things have changed in the UK now, which is why I said “eldest child” talking about today, although the Act is not retrospective and only deals with royal births from 2013 onwards.

A final note is that Margaret Clifford Stanley was to be heir only after H8’s direct heirs (Edward, Mary, & Elizabeth) had each died without heirs of their own. But Margaret died in 1596, thus leaving her two sons as potential heirs. Another potential heir was James VI of Scots, as was his cousin Arabella Stuart, who was in the 1590s a courtier of QE1’s, then of James’ court until she disgraced herself with a secret marriage. When it came down to it, there were quite a few with strong enough claims to QE1’s throne, and the real heir would be the one who got the most powerful folks to back them. And the most powerful men (Burghley and his son Robert Cecil) were happy to keep James dangling, and then eventually Robert put him on the throne, with the help of the Grand Council of Peers (as opposed to Privy Council) convened in March 1603 after QE1’s death. They issued the invitation to James, even signed letters of credit to pay for his travels from Edinburgh to London. Even so powerful a man as Raleigh couldn’t prevail against the Grand Council. And if Cecil had chosen to back some such as Wm. Stanley, he’d have likely won over then too — except that Stanley had no large following and wasn’t yet in possession of his brother’s estates, but James did have vast power and wealth! It came down to that — power and politics over all, not theoretical inheritance principals or long dead kings’ wills. And Cecil stood to gain much more by backing the man with a strong army just across the northern English border, who had already bribed and recruited most of the peers of England. Why fight city hall?

This is a curious one because normally in direct succession a male took precedence to succeed, but any direct child would take precedence in England over a cousin or brother, why, because there is no Salic Law. A woman can sit on the throne no problem. Kings may try to change that with wills and laws, but if there was no son, legally there is nothing to stop a woman from succeeding. Edward tried to mess around by bypassing first his sisters as female and illegitimate, then Frances in favour of Jane Grey, to her male heirs, then it was too late for her to have any as he about to die so he made it Jane and her male heirs, but in fact her sex didn’t prevent her from succeeding, fear of a female ruler being accepted did. But Jane did succeed. Then Mary took her crown back and restored the natural order of succession and some may argue, the lawful one. Mary decided to heed advice and not mess around and as there was no male heirs, her sister, Elizabeth became Queen.

Actually, before they died, the sisters of Jane Grey were the next legal heirs to Elizabeth I, but the line would default to the children of Eleanor Clifford if they were excluded. Although Katherine Grey had living sons, they were not considered legitimate or suitable so hence the default to Margaret Clifford Stanley, Countess of Derby and her sons, Ferdinando and William. As Margaret had died, then Ferdinando died, then his daughter Anne was next, regardless of her sex because there was nothing to stop a woman being Queen. She was the next direct heir to the throne as she was the child of the eldest son. Her uncle only came next if she didn’t have any children. As the Clifford line was obviously not tainted by treason, although there was some suspicions about Margaret and the Derby clan were said to have Catholic sympathy, although I doubt it, as the Montegeals were the Catholic nobles and they hated each other, the children and grandchildren looked good bets for a preferred succession.

James was chosen as part of a deal and a superior claim via both of his parents. Henry Viii’s will may as well have gone in the bin and Elizabeth had her own ideas. Robert Cecil also made certain James was King and the Grand Council agreed. There were others, but he was probably the most sensible and best candidate. Most of the others did not press any claim.

When it came to the Derby estates and title, William inherited the title from his brother because there is tail male clause in the title, so only a male can have it. Anne could inherit many of her family estates and she did. The Isle of Man came to the crown. William was granted Latham and other houses and a long trial and lawsuit followed to sort out the mess.

The situation at Elizabeth’s death in 1603 is intriguing, especially in light of contemporary rumours that the English had tired of queens and were desirous of having a king ruling them. The smoothness of Elizabeth’s succession in 1558 obscures us to the fact that a female accession remained bizarre, for many. After fifty years of continuous female rule (1553-1603), it is entirely possible that traditionalists desired a return to kingship, which led them to prefer the claim of James VI of Scotland.

Elizabeth’s own feelings on the succession remain unclear, but it does seem that she avoided discussing the topic as much as possible. When she was thought to be dying of smallpox in 1562, her councillors were unable to agree on who should succeed her in the event of her death, with some preferring Katherine Grey, one or two suggesting Mary Queen of Scots; even the name of Henry Hastings, earl of Huntingdon, was raised as a possible successor. As her life came to an end in 1603, Elizabeth knew that she had to select an heir before it was too late.

Leanda de Lisle speculates that, unlike her brother, Elizabeth always preferred the claim represented by the Scottish side of her family, the descendants of Henry VIII’s elder sister Margaret. As is well known, Edward VI had chosen the Suffolk line to inherit his throne. From Elizabeth’s point of view, the Suffolk line could not inherit her throne because Katherine Grey’s marriage was invalid and her children were illegitimate. Mary Grey had died childless in 1578. Their cousin Margaret Clifford had been exiled from court in disgrace and had died in 1596.

According to Henry VIII’s last will and testament, Margaret’s granddaughter Anne Stanley was the rightful heir to the throne in 1603, because she was the senior descendant of the Suffolk line. Questions of gender may have come into it, but England had already accepted two successive queens. Elizabeth could well have nominated Anne as her heir, had she wanted to. The contemporary evidence, however, doesn’t suggest that Anne was ever regarded as a serious claimant to the throne.

Instead, there seems to have been a widespread acceptance that James of Scotland was the rightful heir to the throne, although Arbella Stuart’s name was also raised by one or two voices. To me, this acceptance of James’s status suggests that most councillors and courtiers disagreed with Henry VIII’s will, or at the very least believed that it could be amended, or even discarded, according to political, dynastic and religious circumstances. A thirty-six year old Protestant male, who had ruled Scotland since 1567, was definitely preferable to the relatively unknown Anne Stanley, or even to the better known Arbella Stuart.

Scholars interested in the succession to QE1 often overlook the profoundness of how UNPOPULAR she had become in the last half decade of her reign, largely because of the unending war with Spain and the perception of failure of her Netherlands and French policies, wherein King Henri IV had proved rather ungrateful for all the money and men she’d sent to support him. But the crux of the matter was a rebellious Puritan-infested Parliament, which refused to grant her the subsidies she requested, causing her to dismiss it several times, and leading to her dying with some L450,000 in royal debt. Basically, while she continued to pretend to be “Gloriana,” England’s govt was heading toward a financial collapse, with her leaving a bankrupt royal treasury. The war(s) had to end, and most having to make a choice in the succession were fully aware that only James VI of Scots (and his thoroughly-Protestant son Prince Henry) had the gravitas to secure a Spanish peace and return England/UK to a stable economy and a secure place in the world (sort of the opposite of what BREXIT has achieved today!). At first this seemed to come to pass, with a Spanish peace, and Spanish toadies actually gaining James’ trust and much influence at the English Court (e.g., converting Q. Anne and Prince Charles to Catholicism). But the stability lasted only a decade or so before another even greater crisis slowly emerged. Athletic Protestant-hope Prince Henry suddenly died, a series of James’ toy-boy poof favorites gained power over James (e.g., the Pembrokes, Suffolk, & Buckingham), James’ own daughter and son-in-law became chief initiators of the 30-years War (as titular King and Queen of Bohemia), and of course there was the 1623 Spanish Marriage crisis (wherein Buckingham and Prince Charles were essentially kept under house arrest in Madrid!). In short, QE1’s fiscal, economic, social, and moral crisis was never really healed, and only grew worse under James’ tilt toward “the divine right of Kings,” in a real sense causing the mid-century Civil Wars. But in 1598-1603, the majority of Peers in England saw James and his beloved son Prince Henry as the only long-term path to stability, and there was actual resentment that QE1 had “lived too long.”

I understand that King Henry VIII left a will with the succession outlined, but the next king has the right to write his own will for succession, right? So Edward VI could do whatever he wanted, right? Did Mary or Elizabeth have wills in the end?

Yes, Henry VIII left a will in which he put his daughters back in the line of succession. Some historians argue that Edward’s “devise” was not lawful as it hadn’t yet gone through Parliament. However, I think Eric Ives makes a very valid point when he brings up common law and how it prevented bastards inheriting over legitimate claimants, so Edward’s devise was more in keeping with common law.

This my Mothers ancestors…they are in our family tree ( ancestry.com )

Would love to read more