Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

Henry, Lord Darnley, had been lodging at Kirk o' Field while convalescing after contracting either syphilis or smallpox. What he didn't know was that while he had been recovering his enemies had been filling the cellars of the house with gunpowder.

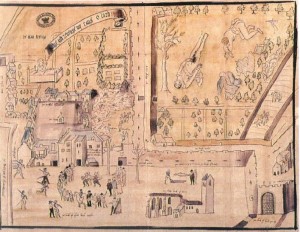

At 2 o'clock in the morning of the 10th February 1567, Kirk o' Field was blown to pieces by a huge explosion which was said to have been heard throughout Edinburgh. The house was reduced to rubble and Darnley's body was found in a neighbouring garden, by a pear tree, beside that of his groom, with a dagger lying on the ground between them.

Historian Magnus Magnusson wrote of how his night-gown clad body showed signs of strangulation and concluded that Darnley had been strangled to death before the explosion. Perhaps something had awoken Darnley and he had attempted to flee the house, with his groom, using the chair and rope, which were also found in the garden, to escape from a first floor window. It appears that both men were intercepted and murdered. Perhaps the explosion was an attempt to cover up their murders but the men had got out of the house before meeting their murderer.

Mary Queen of Scots observed forty days of mourning for her husband, but there were rumours that she was insincere and rumours of murder. It was not long before the Earl of Bothwell's name (James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell) was linked to Darnley's murder as the shoes of Archibald Douglas (Parson of Douglas), a supporter of Bothwell, were found at the scene of the crime and it was alleged that Bothwell had supplied the gunpowder.

On the 24th April 1567, Bothwell and 800 men met Mary on the road between Linlithgow Palace and Edinburgh, and Bothwell warned Mary that there was danger waiting for her in Edinburgh. He then insisted that she go with him to Dunbar, to his castle, so that he could protect her. On arrival at Dunbar at midnight, Bothwell took Mary hostage and allegedly subjected her to a violent rape so that she would marry him. On the 12th May, Mary made Bothwell Duke of Orkney and then married him on the 15th May at Holyrood, just over a week after his divorce from Jean Gordon, Countess of Bothwell, came through. On reporting the events to London, Sir William Drury noted that although it looked as if Mary had been forced into the marriage by Bothwell, things were not as they appeared. There was evidence that Mary had shown an interest in Bothwell in October 1566 when she travelled four hours by horseback to visit him at Hermitage Castle when he was ill. It was all very suspicious.

Mary Stuart and Lord Darnley c.1565, from Hardwick Hall

It is thought that Lord Darnley's murder and Mary's links with Bothwell were factors in her eventual trial and execution. The famous Casket Letters, which were produced at the York Conference in 1568, were said to implicate Mary in Darnley's murder, but many historians now believe that these letters were forgeries. It looks like we will never know whether Mary Queen of Scots played a part in the murder of her husband, Lord Darnley, father of James I of England.

The National Archives have a wonderful report entitled "Kirk o'Field - What happened in 1567" which was produced for teachers but which contains a contemporary sketch of Kirk o'Field (and zoomed in sections), extracts from letters from Mary to Bothwell, and an extract from a letter from Elizabeth I to Mary. Click here to view it now.

The Memorial of Lord Darnley is a painting which was commissioned by Darnley's parents, the Earl and Countess of Lennox, and is viewed as "a damning indictment of the part played by Mary, Queen of Scots, in the murder of her husband and of her association with the Earl of Bothwell and as a cry for vengeance on Darnley’s murderers". Click here to view it and to read more about it.

The Casket Letters

On the 20th June 1567, a few days after Scottish rebels apprehended Mary Queen of Scots, servants of James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton, allegedly found a silver casket of eight letters, two marriage contracts (which apparently proved that Mary had agreed to marry Bothwell before his divorce) and twelve sonnets in the possession of James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell and third husband of Mary Queen of Scots.

What was important about these letters?

Well, the eight letters found in the casket were allegedly written by Mary to Bothwell and one was said to implicate the couple in the murder of Mary's second husband, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, who had been murdered in February 1567. Elizabeth I ordered a commission to investigate the matter of Mary's involvement in Darnley's murder and on the 14th December 1568 the letters were produced at the Royal Commission as proof against Mary.

In his excellent book on Mary Queen of Scots, "My Heart is My Own", historian John Guy writes:

"The sole evidence that she was a part to the murder plot comes from them [the Casket Letters]. There is no other proof. Her guilt or innocence depends on whether the letters are true or false."1

The Casket Letters no longer exist, so cannot be examined today, but we still have the transcripts and translations, complete with William Cecil's notes. It is these notes which Guy says give us a "glimpse" into Cecil's thoughts as he read letters that were "dynamite" in that if they were indeed genuine then "an anointed Queen could justifiably be deposed from her throne, Elizabeth's 'safety' would be guaranteed, and the threat of an international Guise conspiracy ended for ever"2. However, if they were forgeries then Mary would have to be released because it could not be proved that she was complicit in Darnley's murder.

The Sonnets

John Guy writes of how the sonnets found in the casket "were said to be Mary's own reflections on her adultery"3 with Bothwell and proof "that her consuming passion for Bothwell gave her a powerful motive for murder."4 However, Guy points out that they are highly unlikely to be genuine as "they are extremely clumsy and would pass only with the greatest difficulty as the work of a native French speaker"5 and they do not fit with the "genre of courtly love poetry"6 with which Mary was familiar. He also points out that they can be read as religious poetry.

The Marriage Contracts

One of the marriage contracts from the silver casket was said to be dated 5th April 1567 "at Seton", so over a month before Mary and Bothwell's marriage, but Guy points out that this is a "blatant forgery" because the wording of the contract included "extracts from the Ainslie's Tavern bond"7, a document which was produced after the gathering of the Lords at Ainslie's Tavern on the 19th April 1567. The other contract Guy describes as "innocuous" because "it is less a 'contract' than a written promise by Mary to marry Bothwell"8.

The Casket Letters

Letters 1 and 2, "the short Glasgow Letter" and "the long Glasgow letter" were the most damning and the second letter, if genuine, was proof that Mary was Bothwell's lover before their marriage and that she had been involved in Darnley's murder. Letter 2 contained "seemingly graphic allusions to the murder plot... interspersed with its author's protestations of longing and desire for her lover"9 and Guy explains that the case against Mary rested on seven key extracts from the letter. You can read Guy's full thoughts on the letter in "The Casket Letters" chapters of his book, but he argues that only the fifth extract, which said "Think also if you will not find some invention more secret by physick, for he is to take physick at Craigmillar and the baths also. And shall not come forth of a long time"10, can be connected to a murder plot. Guy explains that this extract was meant to prove that Mary wanted Darnley to be poisoned while he was at Craigmillar but it is not evidence of the plot which actually killed Darnley at Kirk o'Field. Also, Guy argues that "it has to be regarded as a later forged interpolation"11 because it was missed in the material that was sent by George Buchanan to William Cecil in June 1568 and only used in the final accusations laid against Mary by the Confederate Lords to prove that Darnley's illness, which was in fact syphilis, was caused by poisoning. This charge does not make sense though as Darnley was already ill at this time.

After examination of the transcripts and translations, Guy concludes that, "in the absence of the original handwritten pages" of Letter 2, "around 1500-1800 words are likely to be genuine" and that 1000-1200 words are "likely to interpolations"12 from later letters or forgeries. It could well be that "old and new pages were spliced together to make up a composite document"13 to convince Cecil and Elizabeth of Mary's guilt.

The controversy and debate over these letters still continues today and I would recommend John Guy's book "My Heart is My Own: The Life of Mary Queen of Scots" to anyone interested in The Casket Letters or Mary Queen of Scots in general.

If you're a subscriber to British History Online, you can view the Casket Letters in Appendix 2 of the Calendar of State Papers, Scotland: Volume 2, 1563-69, ed. Joseph Bain (London, 1900), pp. 722-731 - click here. You can also read some of what was in the casket in An examination of the letters, said to be written by Mary queen of Scots, to James Earl Bothwell: Volume II ed. Walter Goodall and Collections Relating to the History Of Mary Queen of Scotland: Volume II, ed. James Anderson.

Notes and Sources

- My Heart is My Own: The Life of Mary Queen of Scots, John Guy, p396

- Ibid., p398

- Ibid., p399

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p400

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p404

- Ibid., p413

- Ibid., p415

- Ibid., p416

- Ibid., p417

this is all wrong we dont know if it was mary and bothwell!!!!!!

But I don’t say it was Mary and Bothwell. I write that there were rumours Mary was involved, I write that Bothwell’s name soon becamse linked to the murder, I write that letters were said to implicate Mary in the murder but that these are now thought to be forgeries, and I conclude “It looks like we will never know whether Mary Queen of Scots played a part in the murder of her husband, Lord Darnley, father of James I of England.”

If the casket letters are forgeries, who wrote them and why?

Possibly James Stuart, Earl of Moray, Mary’s illegitimate half-brother. Guy proposed that “Moray and his allies knew that they’d never get away with outright forgeries, so to satisfy Elizabeth and establish Mary’s guilt, they needed carefully to select pages of genuine letters that, once mixed up and doctored, would seem to clinch what they sought to prove. This hypothesis explains the curious incongruities”.

Many people did not like Mary, a) because she was a woman, and had no heir and b) because she was a Catholic. It would suit Mary’s half-brother, James Stuart, if she was executed for murder, as he could very possibly be put on the Scottish throne. Queen Elizabeth had sent Darnley to Scotland as a suitor, however pretty he was considered, he was a poor choice for a husband, because he was not rich, only a minor noble, and had no men or armies to add to Scotland’s forces. If Mary had married, for example, a Spanish prince, she would have been a definite threat to England. Mary wrote and allegedly said some unkind things about Darnley after he stabbed Rizzio, one of her friends, and an Italian ambassador to death. When Darnley became sick, she had him moved to the place where she was staying, which was uncharacteristic. The only proof of Mary’s part in Darnley’s murder are the Casket Letters, though her actions after his death were suspicious, as she was hesitant to investigate his murder, and married Bothwell after observing only 40 days of mourning. Mary was eventually killed because Elizabeth I and her advisors deemed the letters, among other things, proof of her traitorous nature, and had her executed for plotting to take the English throne. Because we do not have the original Casket Letters, is it very hard to determine who wrote them, and also becuase it was so long ago.

Mary was also a threat to Elizabeth’s throne, because she was Catholic. Egland was protestant at the time, however there were many people who dissaproved of the new religion and would like to see a Catholic queen in charge. This is why Elizabeth put Mary under house arrest, making her much less of a threat. After 18 years, Elizabeth had Mary killed for plotting to take her throne, after letters allegedly from Mary were intercepted, and it was found she was plotting to take the throne. However, these letters, also could have been forged.

Excellent article, thanks. I have always been suspicious of the Casket Letters, although I feel it was foolish of Mary to marry Bothwell when he was implicated in her husband’s murder. I know Mary had come to hate and fear Darnley as a murderer and violent drunk, but it’s unlikely that she would kill him. Darnley turned out to be a disappointment for those who made him King and they had turned on him. He had plenty of enemies willing to bunk him off. Mary, herself was ill with smallpox at the same time, although she recovered and the 1568 investigation did not convict her. The letters were used later at her trial. Mary had growing enemies; she needed to escape, Bothwell offered protection. It’s impossible that she would have married him unless he forced her to and I do believe he raped her. What a cruel and insensitive man, divorcing his wife, Jean Gordon who welcomed Mary into her home and then marrying the Queen!..I can see why the Puritan Lords now saw Mary as a hussy and believed that she had married her lover and accomplish. First, these Lords now had an excuse to oust Mary, of whom many disapproved. Second, Mary had fallen into their trap by wedding Bothwell. Third, Mary could have played the victim better by appealing to the Lords and council for help, putting her case as a wronged woman to them and demanding that they rescue her from Bothwell and arrest him as her abuser and a murderer. A bit of helpless woman, appealing to the good Lords of the Congregation, boo hoo, tears, sorrow, tears, help me, my lords, justice…may have saved her. Instead Mary looked guilty because she did nothing. She tried to explain, but she didn’t ask or demand action against Bothwell. This made her look suspicious when she fled to her cousin in England for help. Women are worse than men when it comes to hurling mud and throwing blame and shame at another woman, so she took a great risk in asking Elizabeth to help her. Elizabeth also found Mary an annoyance she could do without as Mary undermined her sovereignty over England, by calling herself Queen of England. Elizabeth was not happy Mary was here, but she pretended to welcome her, while keeping her in ‘protective custody’ for eighteen years before executing her sister Queen on trumped up charges of treason.

To be honest I don’t think Elizabeth really knew what to do with Mary. She couldn’t send her back to Scotland, that would be a disaster for both of them and she couldn’t provide her with ships to go to France, not without risking her return at the head of a French Armarda. If Mary cleared herself, Elizabeth promised to her her cause and meet her, but she decided that she could not risk that either.

ok

The thing with Elizabeth and Mary was:

Remember Henry the Eighth? Well, he wanted to divorce his wife, but the Pope said no, so he then created a new church: the Church of England. He was Elizabeth’s father.

Many people in England at the time thought that Elizabeth was not the true monarch because her father divorced and re married, and they believed that was against God. Mary was Catholic however, and so it was possible that those very people could try and make Mary queen instead of Elizabeth.

Elizabeth played her hand very smartly, I think. She welcomed Mary when she fled to England, and then put her under house arrest, meaning she was controlled and no longer a threat, and all without killing her.

BUT, remember those Catholics who liked the idea as Mary for Queen? Well, they start writing Mary letters, saying that she should overthrow Elizabeth, and stupidly, Mary responds. (Keep in mind that it is possible that all of these letters were forged to frame Mary) Elizabeth then has no choice but to kill Mary.

does anyone have any ideas in why the chair and the dager were there and why they were half naked?

The chair it is thought was used along with the rope to lower Darnley (who was ill, if you recall) out of the window. I am not sure of the dagger. They were in their nightclothes, suggesting they had had to escape with very little time. Darnley, strangely enough, was not killed by the blast and was instead strangled to death. there are theories that either he escaped the blast that was meant to kill hima dnt then had to be killed by another means, or that the blast was a diversion.

I am sketching out the outline for a possible play about Mary Stuart. I have a question about the murder of Darnley: where did the gunpowder that blew up Kirk o’ Field come from? (There couldn’t have been much of it in Scotland at the time; the military authorities in practically every European country were constantly complaining about the short supply available to them.) Also: why would anybody planning a murder in sixteenth-century Scotland EVER hit upon gunpowder as a murder weapon? Gunpowder has every imaginable disadvantage as a lethal agent: it’s expensive, it’s cumbersome (requiring several strong men to move it, which means increasing the number of men who are “in the know”), and it’s bulky, which makes it harder to hide. Also, Darnley was killed in the middle of winter — a Scottish winter. If gunpowder were stored in a cellar (as it would have to be, to destroy a building), its surroundings would be EXTREMELY damp, if not downright wet — which meant that the powder would be in constant danger of losing its ginger and failing to explode. (Drying out the cellar wouldn’t be an option: the only way to dry out a room in Scotland in wintertime in that era was to keep a roaring fire burning in the fireplace for two or three days, and cellars didn’t have fireplaces). When the Scottish nobles wanted to kill someone, they used their dirks or their swords, as they had the previous year when they murdered Ricciardi.

Any thoughts you have on any of the above observations would be welcome.

While it is not exactly clear where the gunpowder was bought, barrels upon barrels of it were blown up from the cellars of the house Darnley was staying in.

Hi,

I am looking for information on Henry Stuart’s illegitimate children, for a family tree, does anyone here have any information that could be of use?

it is known that the gunpowder was stored in the cellar underneath lord darnleys sleeping keyboards

And we thought WorldStar and Real Housewives of Atlanta were ratchet. Other than missing the crown, posh accent, etc, seems ratchet is something that exists everywhere.