In my article on Margaret Clifford, Countess of Derby, I noted that Margaret has been neglected by historians and novelists alike. Both Margaret and her mother Eleanor Brandon, Countess of Cumberland, have been marginalised in both fiction and non-fiction, especially when compared with other royal women of the period such as Lady Jane Grey and her sisters, Lady Margaret Douglas and, of course, Henry VIII’s six wives. The academic and popular fascination with the Grey family is explicable in view of their dynastic importance during the reigns of Edward VI and Elizabeth I; during Edward’s reign, Jane Grey was named heiress to the throne and would have reigned as queen of England had it not been for the extraordinary success of Mary Tudor’s coup in the summer of 1553. Jane’s sister Katherine was widely regarded as a viable successor to Elizabeth I, which enraged and unnerved the Tudor queen. After clandestinely marrying Edward Seymour, Katherine was incarcerated in the Tower of London, her marriage declared invalid and her children deemed to be illegitimate. More recently, Lady Margaret Douglas has attracted the interest of historians and novelists; as the mother-in-law of Mary Queen of Scots and the grandmother of James I of Scotland, this interest is perhaps not surprising.

By contrast, both Margaret Clifford and her mother Eleanor Brandon are relatively unknown Tudor women. Yet Eleanor, like her more well-known sister Frances, was a niece of Henry VIII and a granddaughter of Henry VII. She was the younger daughter of Mary Tudor, Duchess of Suffolk and formerly queen consort of France, and her husband, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. During Edward VI’s reign, Eleanor was seventh-in-line to the English throne. Her dynastic and political importance was minimal compared to that of her sister and nieces, but Eleanor’s story nonetheless deserves attention.

Eleanor was born in 1519 at Westhorpe Hall in Suffolk, where she probably spent most of her childhood. Both she and her elder sister Frances would have received a conventional education, in which they acquired the feminine skills of dancing, singing, needlework and the courtly graces; it is also possible that Eleanor received instruction in French. It is likely that Eleanor occasionally visited court. An Elizabethan Jesuit later recorded that she and Frances were the ‘favourite nieces’ of Henry VIII, which indicates that they enjoyed good relations with their uncle. Certainly, this would appear to make sense given both Margaret Douglas’s escapades and Henry VIII’s decision to nominate his Brandon nieces as his heirs to the throne if his three children proved childless. In the spring of 1533, when she was fourteen, Eleanor was betrothed to Henry Clifford, later second Earl of Cumberland. Clifford was two years Eleanor’s senior and resided mainly at the family’s home at Skipton Castle in Yorkshire. He was said to be ‘tall and slender’ in appearance and ‘studious’ in nature. Clifford’s activities during Elizabeth I’s reign provide evidence of his Catholic sympathies. He was rumoured to be sympathetic to Catholic priests and was thought to be supportive of the Northern Rebellion in 1569. Unfortunately for Eleanor, her mother died at Westhorpe Hall a few months after her betrothal. Mary, Duchess of Suffolk, was a passionate and opinionated woman, but we have no way of knowing whether she was close to her daughters.

During her youth, Eleanor participated in court festivals. At the funeral of Henry VIII’s first wife Katherine of Aragon in January 1536, Eleanor was present as chief mourner. Probably later that year, her marriage to Clifford took place in the king’s presence. Little is known about the married life of Clifford and Eleanor, but they resided at Skipton Castle after their wedding. The earl and countess may also have spent time at Brougham Castle in Cumbria. In an extant letter, Eleanor referred to her husband as ‘dear heart’ and signed herself as ‘your assured loving wife’. The couple had three children: Margaret (born in 1540), Henry and Charles; both sons died before reaching adulthood. Skipton Castle was an imposing residence that had been built in 1090, but it is unclear whether Eleanor enjoyed living there or whether she would have preferred a life at court. In the autumn of 1536, rebellion broke out in northern England, motivated mainly by opposition to the Henrician regime’s religious and social reforms, especially in relation to the dissolution of the monasteries. Both Eleanor’s husband and her father-in-law refused to lend support to the Pilgrimage of Grace, as the rebellion became known, and they fortified Skipton in anticipation of an assault on the castle by the rebels. Clifford travelled to Carlisle to defend the city, and Eleanor departed for Bolton Abbey in search of refuge. Skipton Castle was besieged on 22 October, and the rebels seized the countess, her young son (perhaps Henry), and sisters-in-law at Bolton Abbey. The rebels threatened Eleanor’s father-in-law that if he did not surrender Skipton to them, the countess would be violated to his ‘discomfort’. Fortunately for Eleanor, Christopher Aske concluded negotiations with Clifford, and Eleanor departed from Bolton Abbey to Skipton Castle. The rebels subsequently abandoned their siege of the castle.

Little is known of the last decade of the countess’s life. Her mother had been sympathetic to Katherine of Aragon, Henry VIII’s first wife, and it is intriguing that Eleanor took a senior ceremonial role at Katherine’s funeral; it is impossible, however, to ascertain her relationship with Katherine or with any of Henry VIII’s other wives. Her uncle died on 28 January 1547 and her nephew, the nine-year-old Edward, succeeded him as king of England. Eleanor died on 27 September 1547 at the age of twenty-eight. Nicola Tallis has suggested that Eleanor may have died of pancreatic cancer; her surviving letter to Clifford alluded to her red ‘water’ and ‘pains in my side’, which she attributed to ‘the jaundice and the ague both’. She was buried at the Church of Holy Trinity in Skipton. In the seventeenth century, the countess’s remains were discovered; they apparently indicated that she had been ‘very tall and large boned’.

Clifford remarried after his wife’s death; his second wife was Anne Dacre, by whom he had three children. Six years after Eleanor Brandon’s death, Edward VI died and her niece Jane Grey was proclaimed queen of England. The teenage king had been determined to prevent either of his illegitimate half-sisters from succeeding him; like his father, he favoured the descendants of Henry VIII’s younger sister Mary over the descendants of Henry’s elder sister Margaret. The Suffolk line, however, was not fated to enjoy the crown of England. Jane Grey was executed during Mary I’s reign and Eleanor’s brother-in-law Henry Grey was beheaded eleven days after his daughter’s execution. Eleanor’s nieces Katherine and Mary Grey were both imprisoned during the reign of Elizabeth I for marrying without royal permission. Katherine’s marriage was declared invalid, and her children were deemed illegitimate, which effectively prevented them from being viewed as possible successors to Elizabeth.

According to the last will and testament of Henry VIII, with Mary Grey’s death in 1578, Elizabeth’s heir was Margaret Stanley, daughter of Eleanor Brandon. The fragmentary evidence indicates that Eleanor’s daughter was ambitious and aspired to be Queen of England after the death of Queen Elizabeth. She was accused of using sorcery to predict the queen’s death and was subsequently placed under house arrest. Margaret never regained royal favour and died in 1596. Whether Elizabeth would have named Margaret as her heir is unclear, but if Margaret had succeeded her cousin as queen in 1603, at the age of sixty-three, then Eleanor might have been more well-known in both academic and popular circles as the mother of an English monarch. The treasonous actions of the Suffolk line, however (including Margaret’s disgrace), and Clifford’s alleged Catholic sympathies almost certainly mean that the English queen would never have selected Margaret Clifford as her heir. Leanda de Lisle has speculated that Elizabeth always preferred the claim of James VI of Scotland to that of the Suffolk side of the family.

According to Henry VIII’s will and the wishes of Edward VI, who had also preferred the Suffolk line, Elizabeth I’s rightful heir at her death in 1603 was Anne Stanley, granddaughter of Margaret Clifford and great-granddaughter of Eleanor Brandon. By instead naming James VI of Scotland as her heir, Elizabeth explicitly ignored the wishes of both her father and brother. From a legal and constitutional perspective, the descendants of Eleanor Brandon should rightfully have sat on the throne of England after the death of Elizabeth I.

Conor Byrne studied at the universities of Exeter and York. He specialises in late medieval and early modern English history, with an emphasis on royal history, gender relations and Tudor queenship. His first book, Katherine Howard: A New History (2014) was published by MadeGlobal and has been described as ‘a brilliant study’, ‘a new and refreshing biography of Katherine Howard’ and ‘a timely addition to Tudor scholarship’. Conor’s second book Queenship in England (2017) was also published by MadeGlobal and provides an in-depth analysis of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century queenship. He runs an active Facebook page at www.facebook.com/ConorByrneHistorian.

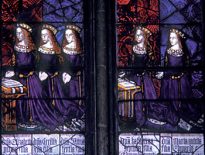

Pictures: Skipton Castle, ca. 1890 - 1900, The Library of Congress, Wikipedia; The Yarnborough Portrait of Mary Tudor, Queen of France, and Charles Brandon; Portrait of an unknown woman, possibly Eleanor Brandon or her daughter Margaret Clifford, by Hans Eworth. The style of costume indicates that it is more likely to represent Margaret.

My three visits to Skipton (one in the wind and rain and one during the Christmas market and one Summer that was glorious, I loved the castle and church were Eleanor is buried and it wasn’t hard to imagine the state rooms, especially as the none public part of the castle gives a good idea of how they might have looked. Boulton Abbey is also pretty impressive. I know the story well about Eleanor and her infant son being held hostage and Ask’s own brother, Sir Christopher being sent to rescue them. Henry Viii also wrote a letter to the young future Earl, Henry Clifford, who was left to defend the Castle as the Earl had gone to put down a band of approaching rebels, commending his bravery. Some 50 retainers joined the rebels, so strong was the feeling in the counties against the monasteries being dissolved and religious changes. Ironically it was partly due to these Pilgrimages of Grace that Henry then used as an excuse to Dissolve the Greater Monastic Houses.

It may seem to some people that all all this was a big fuss, but if you had only known one religious life, one Mass, one prayer book, tuned your life to the marking of the hours, to hearing the service sung, to the Great Monastery on the Landscape, to set festivals every year and had always done so, loved the beauty of those buildings, went as a patroness regularly to them and so on, you would protest also about losing them. The King is also so far away, you think he does not listen to your plight, but has been taken over by evil counsel, that his new ministers are giving him bad advice, but if you go to London with large numbers of ordinary people, he may meet with you and hear you. The King is the seat of justice. He will listen and do the right thing, will he not?

There was a problem. Henry liked the advice he was getting from Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Audley, it made him very rich and he hated this kind of large spread semi violent opposition to his own God given authority. Henry would pretend to listen, have Robert Aske and John Constable for Christmas, receive a full list of demands, then he would tell them he would do everything they asked and pardoned everyone. They all went home. Ah, but some rose again and smelled a rat and attacked the Clifford’s other stronghold. They found it was a trap. 700 were either killed, taken prisoner or fled. After this Henry struck back, hard.

Eleanor is for me more interesting because she is the family mystery. Her adventures during the Pilgrimage of Grace bring her to the forefront of history for a brief time and then she fades again. Her two sons died young and her daughter emerges as an important heiress to Queen Elizabeth, one of those who should have followed before Mary Queen of Scots and her son James. Margaret made a Cross for her mother half way between where she died and Skipton and she is also on there as a mourner. I can’t remember where but it will come to me. Her granddaughter, Lady Anne Clifford wrote the famous seventeenth century source Her Diary and Letters. I think her grandson, Sir George Clifford is the famous dandy in the armour who is the Champion of Queen Elizabeth. Yes, we only have snippets of Eleanor and her family and her life. I do wish someone would write a biography of both her and Frances. Although we know more about Frances through her famous daughters, she too has been overlooked as far as a biography being available. Perhaps Conor or Nicola would like this as their next project?

I would certainly buy it. Thanks for this article. Well over due.