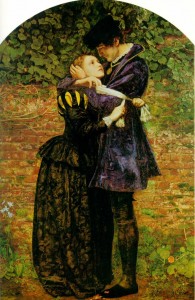

A Huguenot, on St. Bartholomew's Day, Refusing to Shield Himself from Danger by Wearing the Roman Catholic Badge (1852) by John Everett Millais

Eye witness account, written by historian Jacques Auguste de Thou

So it was determined to exterminate all the Protestants and the plan was approved by the queen. They discussed for some time whether they should make an exception of the king of Navarre and the prince of Condé. All agreed that the king of Navarre should be spared by reason of the royal dignity and the new alliance. The duke of Guise, who was put in full command of the enterprise, summoned by night several captains of the Catholic Swiss mercenaries from the five little cantons, and some commanders of French companies, and told them that it was the will of the king that, according to God's will, they should take vengeance on the band of rebels while they had the beasts in the toils. Victory was easy and the booty great and to be obtained without danger. The signal to commence the massacre should be given by the bell of the palace, and the marks by which they should recognize each other in the darkness were a bit of white linen tied around the left arm and a white cross on the hat.

Meanwhile Coligny awoke and recognized from the noise that a riot was taking place. Nevertheless he remained assured of the king's good will, being persuaded thereof either by his credulity or by Teligny, his son-in-law: be believed the populace had been stirred up by the Guises and that quiet would be restored as soon as it was seen that soldiers of the guard, under the command of Cosseins, bad been detailed to protect him and guard his property.

But when he perceived that the noise increased and that some one had fired an arquebus in the courtyard of his dwelling, then at length, conjecturing what it might be, but too late, he arose from his bed and having put on his dressing gown he said his prayers, leaning against the wall. Labonne held the key of the house, and when Cosseins commanded him, in the king's name, to open the door he obeyed at once without fear and apprehending nothing. But scarcely had Cosseins entered when Labonne, who stood in his way, was killed with a dagger thrust. The Swiss who were in the courtyard, when they saw this, fled into the house and closed the door, piling against it tables and all the furniture they could find. It was in the first scrimmage that a Swiss was killed with a ball from an arquebus fired by one of Cosseins' people. But finally the conspirators broke through the door and mounted the stairway, Cosseins, Attin, Corberan de Cordillac, Seigneur de Sarlabous, first captains of the regiment of the guards, Achilles Petrucci of Siena, all armed with cuirasses, and Besme the German, who had been brought up as a page in the house of Guise; for the duke of Guise was lodged at court, together with the great nobles and others who accompanied him.

After Coligny had said his prayers with Merlin the minister, he said, without any appearance of alarm, to those who were present (and almost all were surgeons, for few of them were of his retinue): "I see clearly that which they seek, and I am ready steadfastly to suffer that death which I have never feared and which for a long time past I have pictured to myself. I consider myself happy in feeling the approach of death and in being ready to die in God, by whose grace I hope for the life everlasting. I have no further need of human succor. Go then from this place, my friends, as quickly as you may, for fear lest you shall be involved in my misfortune, and that some day your wives shall curse me as the author of your loss. For me it is enough that God is here, to whose goodness I commend my soul, which is so soon to issue from my body. After these words they ascended to an upper room, whence they sought safety in flight here and there over the roofs.

Meanwhile the conspirators; having burst through the door of the chamber, entered, and when Besme, sword in hand, had demanded of Coligny, who stood near the door, "Are you Coligny ?" Coligny replied, "Yes, I am he," with fearless countenance. "But you, young man, respect these white hairs. What is it you would do? You cannot shorten by many days this life of mine." As he spoke, Besme gave him a sword thrust through the body, and having withdrawn his sword, another thrust in the mouth, by which his face was disfigured. So Coligny fell, killed with many thrusts. Others have written that Coligny in dying pronounced as though in anger these words: "Would that I might at least die at the hands of a soldier and not of a valet." But Attin, one of the murderers, has reported as I have written, and added that he never saw any one less afraid in so great a peril, nor die more steadfastly.

Then the duke of Guise inquired of Besme from the courtyard if the thing were done, and when Besme answered him that it was, the duke replied that the Chevalier d'Angouleme was unable to believe it unless he saw it; and at the same time that he made the inquiry they threw the body through the window into the courtyard, disfigured as it was with blood. When the Chevalier d'Angouleme, who could scarcely believe his eyes, had wiped away with a cloth the blood which overran the face and finally had recognized him, some say that he spurned the body with his foot. However this may be, when he left the house with his followers he said: "Cheer up, my friends! Let us do thoroughly that which we have begun. The king commands it." He frequently repeated these words, and as soon as they had caused the bell of the palace clock to ring, on every side arose the cry, "To arms !" and the people ran to the house of Coligny. After his body had been treated to all sorts of insults, they threw it into a neighboring stable, and finally cut off his head, which they sent to Rome. They also shamefully mutilated him, and dragged his body through the streets to the bank of the Seine, a thing which he had formerly almost prophesied, although he did not think of anything like this.

As some children were in the act of throwing the body into the river, it was dragged out and placed upon the gibbet of Montfaucon, where it hung by the feet in chains of iron; and then they built a fire beneath, by which he was burned without being consumed; so that he was, so to speak, tortured with all the elements, since he was killed upon the earth, thrown into the water, placed upon the fire, and finally put to hang in the air. After he had served for several days as a spectacle to gratify the hate of many and arouse the just indignation of many others, who reckoned that this fury of the people would cost the king and France many a sorrowful day, Francois de Montmorency, who was nearly related to the dead man, and still more his friend, and who moreover had escaped the danger in time, had him taken by night from the gibbet by trusty men and carried to Chantilly, where he was buried in the chapel.

Transcribed from De Thou, Histoire des choses arrivees de son temps, (Paris, 1659), in Readings in European History, 2 vols. J.H. Robinson, ed., Boston: Ginn, 1906, 2:179-183. Source: Hanover Historical Texts Project

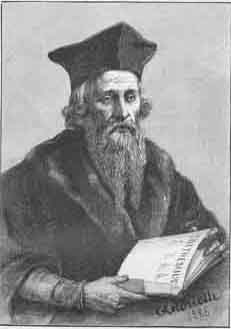

John Foxe

A briefe Note concerning the horrible Massaker in Fraunce. an. 1572:

Here before the closing vppe of this booke, in no case woulde bee vnremembred the tragicall and furious Massaker in Fraunce, wherein were murdered so many hundrethes, and thousands of Gods good Martyrs. But because the true narration of this lamentable story is set forth in english at large, in a booke by it selfe, and extant in print already, it shall the lesse neede now to discourse that matter with any new repetition: only a briefe touch of summary notes for remembraunce maye suffice. And first for breuity sake, to ouerpasse the bloudy bouchery of the Romish Catholickes in Orynge, agaynst the Protestantes, most fiercely and vnawares breaking into theyr houses, and there without mercy killing man, woman & child: of whom some being spoyled and naked they threw out of theyr loftes into the streetes, some they smothered in theyr houses with smoake, with sword & weapon, sparing none, the karkases of some they threwe to dogges which was an. 1570. in the reign of Charles 9. Likewyse to passeouer the cruell slaughter at Rhoane, whereas the Protestants being at a Sermon without the City Wals vpon the kings edict, the Catholiques in fury ranne vpon them comming home, and slew of them aboue 40. at least, many moe they wounded. This example of Roane styrred vp the Papists in Dyepe to practise the like rage also agaynst the Christians there returning from the sermon, whose slaughter had bene the greater, had they not more wisely before bene prouided of weapon, for theyr own defence at need. All which happened about the same yeare aforesayd. an. 1570. but these with such like I briefly ouerslippe, to enter now into the matter aboue promised, that is briefly to entreat of the horrible and most barbarous massaker wroughte in Paris, suche as I suppose, was neuer heard of before in no ciuill dissention amōgest the very heathen. In few wordes to touch the substaunce of the matter.

After long troubles in Fraunce, the Catholique side foreseing no good to be done agaynst the Protestantes by open force, began to deuise how by crafty meanes to entrap them.

And that by two maner of wayes: The one by pretending a power to be sent into the lower countrey, wherof the Amirall to be the Captayne, not that the king so meant in deed, but onely to vnderstand thereby, what power and force the Amirall hadde vnder him, who they were, and what were theyr names. The second was by a certeine mariage suborned, betwene the Prince of Nauare, and the kinges sister. To this pretensed mariage, it was deuised that all the chiefest Protestantes of Fraunce shoulde be inuited, and meete in Paris. Emong whome first they began with the Queene of Nauare, Mother to the Prince, that should mary the kings sister, attempting by all meanes possible to obteine her consent thereunto. She being then at Rochell, and allured by many fayre wordes to repayre vnto the king, consented at length to come, and was receiued at Paris, where she after much a do, at length being wonne to the kinges minde, and prouiding for the mariage, shortly vpon the same fell sicke, & within fiue daies departed: not without suspitiō, as some sayd, of poyson. But her body being opened, no signe of poyson could there be founde, saue onely that a certayne Poticary made his brag that he had killed the Queene, by certayne venemous odours and smelles by hym confected.

After this notwithstanding the mariage still goyng forward, the Amirall, Prince of Nauare, Condee, wyth diuers other chiefe states of the Protestantes, induced by the kinges letters and many fayre promises, at last were brought to Paris. Where with great solēnity they were receiued, but especially the Amirall. To make the matter short. The day of the mariage came, which was the 18. of August. an. 1572. which mariage being celebrate and solēnised by the Cardinall of Borbone, vpon an high stage set vp of purpose without the Churthe walles, the Prince of Nauare, & Condee, came downe, wayting for the kinges sister being then at Masse. This done, they resorted altogether to the Bishops Palace, to dinner. At euening they were had to a Palace in the middle of Paris to Supper. Not long after this, being the 22. of August, the Amirall comming from the Counsell table, by the way was stroken with a Pistolet charged with iij. pellets, in both hys armes. He being thus wounded and yet still remayning in Paris, although the Vidam gaue him counsell to flye away, it so fell out that certayne souldiors were appoynted in diuers places of the Citty to be ready at a watchword at the commaundemēt of the Prince. Vpon which watchword geuē, they burst out to the slaughter of þe protestantes, first beginning with the Amirall himselfe, who being wounded with many sore woundes was cast oute of the window into the street, where his head being first stroken of, and imbalmed with spices to bee sent to the Pope, the sauadge people raging agaynst him, cut of hys armes and priuy members, and so drawing him 3. dayes through the streetes of Paris, they dragged him to þe place of execution, out of the City, and there hanged him vp by his heeles to the greater shew and scorne of him.

After the Martyrdome of this good man, the armed souldiours with rage and violence ranne vpon all other of the same profession, slaying and killing all the Protestantes they knew or coulde finde within the Citty gates inclosed. This bloudye slaughter continued the space of many dayes, but especially the greatest slaughter was in the three first dayes, in which were numbred to be slayne, as the story writeth, aboue x. thousand, men and women, old and young, of all sorts and conditions. The bodies of the dead were caryed in Cartes to be throwne in the Riuer, so that not onely the Riuer was all steined therwith, but also whole streames in certayn places of the City did runne with goare bloud of the slayne bodyes. So greate was the outrage of that Heathenish persecution, that not onely the Protestantes, but also certayne whome they thought indifferent Papists they put to the sword in sted of Protestantes. In the number of them that were slayne of the more learned sort, was Petrus Ramus, also Lambinus an other notorious learned man, Plateanus, Lomenius, Chapesius,

with others.

And not onely within the walles of Paris this vprore was conteined but extended farther into other cities and quarters of the Realme, especially Lyons, Orliens, Tholous, and Roane. In which cities it is almost incredible, nor scarse euer heard of in any natiō, what crueltye was shewed, what numbers of good men were destroyed in so much that with in the space of one moneth xxx. thousand at least of religious Protestantes are numbred to be slayne, as is crediblely reported and storyed in the cōmētaryes of them which testify purposely of that matter.

Furthermore here is to be noted, that when the Pope first heard of this bloudy styrre, he with his Cardinalles made such ioy at Rome, with theyr procession, with their gunshot and singing Te Deum, that in honor of that festiuall acte, a iubilee was commaunded by the Pope wyth great indulgence, and much solemnity, wherby thou hast here to discerne, and iudge, with what spirite and charity these Catholiques are moued to mainteine their religion withall, which otherwise would fall to the ground with out all hope of recouery. Likewise in Fraunce no lesse reioysing there was vpon the xxviij. day of the sayd Moneth, the king commaunding publique processions thorow the whole City to be made, with bonefires, ringing and singing, where the king himselfe, with the Queene his mother, and his whole Court resorting together to the Church, gaue thankes and laud to GOD, for that so worthy victory atchieued vpon S. Bartholomews day agaynst the Protestantes, whome they thought to be vtterly ouerthrowne and vanquished in all that Realme for euer.

And in very deede to mans thinking might appeare no lesse after such a great destruction of the Protestantes hauing lost so many worthy and noble captaynes as thē were cutte of, whereupon many for feare reuoking their religion, returned to the pope, diuers fled out of þe realme such as would not turn, keeping themselues secret, durst not be knowne nor seene, so that it was past all hope of man, that the Gospell shoulde euer haue any more place in Fraunce: but suche is the admirable working of the Lord, where mans helpe and hope most fayleth there hee most sheweth his strength and helpeth, as here is to bee seene and noted. For where as the litle small remnant of the Gospell side, being now brought to vtter desperation were now ready to geue ouer vnto the king, and many were gone already agaynst cōscience, yelding to time, yet the Lord of his goodnes so wrought, that many were stayed and reclaymed agayne through the occasion first of them in Rochell: Who hearing of the cruell massaker in Paris, and slaughter at Tholous, most constantly with valiaunt hartes (the Lord so working) thought to stand to theyr defence agaynst the kinges power, by whose example certayne other Cities, hearing therof tooke no litle courage to do the like, as namely Montalbane, the Citty called Nemansium, Sansere in Occitamia, Milialdum, Mirebellum, Fuduzia, with other townes and Citties moe: who being confederate together, exhorted one an other to be circumspect and take good heede of the false dissembling practises not to be trusted of the mercilese papistes, entending nothing but bloud and destruction.

These thinges thus passing at Rochell, the king hearing thereof, geueth in commaundement to Capteyne Strozzius, & Guardius

to see to Rochell. After thys he sendeth a noble man one Biromus, requiring of the Rochell men to receiue him for theyr Gouernour vnder the king. Of this great consultation being had, at length the Rochell men began to condescend vpon certayne conditions, which being not easily graunted vnto, and especially they hearing in the mean time what was done to others of theyr felowes, which had submitted themselues, thought it so better to stand to the defence of theyr liues & consciences and to aduenture the worst.

Whereupon began great siege and battery to be layde agaynste Rochell both by land and sea, which was an, 1572. about the 4. day of December, it woulde require an other volume, to describe all thinges, during the time of the siege, þt passed on either side, betwene the kinges part, and the towne of Rochell, briefly to runne ouer some parts of the matter. In the beginning of the next yeare folowing, which was an. 1573. in the moneth of Ianuary cōmaundement was geuen out by the king to all and sondry nobles and piers of Fraunce, vpon great punishment, to addresse themselues in moste forceable wise to the assaulting of Rochell. Wherupon a great concourse of all the nobility, with the whole power of Fraunce, was there assembled, amongst whom was also the Prince of Aniow, the kinges Brother (who there not long after was proclaymed kyng of Polonie) accompanied with his other Brother Duke Alanson, Nauare, Condie, & other a great nūber of states besides. Thus the whole power of Fraūce being gathered agaynst one poore Towne, had not the mighty hande of the Lord stood on theyr side, it had bene vnpossible for thē to escape. Duryng the time of this siege, which lasted about 7. monethes, what skirmishes and conflicts were on both sides, it would requyre a lōg tractatiō. To make short, 7. principal assaults were geuen to the poore town of Rochell, with all the power that Fraunce could make. In all which assaultes euer the Popes catholick side had the worst. Concerning the first assault thus I finde written, that within the space of xxvj. dayes, were charged agaynst the walles and houses of Rochell, to the number of xxx. thousand shot of yron bullets and globes, wherby a great breach was made for the aduersary to inuade the City: but such was the courage of them within, not men onely, but also of women, matrons, and maydens with spits, fire, & such other weapon as came to hande, that the aduersary was driuen backe, with no small slaughter of theyr souldiours: onely of the townesmen were slayne & wounded to the number of lx. persons. Likewise in the secōd assault 2000.great fielde peaces were layde against the towne, whereupon the aduersary attempted the next day to inuade the towne: but through the industry of the souldiors and citizens, and also of women and maydes, the inuaders were forced at length to flye away faster thē they came. No better successe had all the assaults that folowed: Wherby consider (gentle reader) with thy selfe in what great distresse these good men were in, not of Rochell onely, but of other Cityes also, during these 7. Monethes aboue mentioned, had not the mighty hand of the Lord almighty susteined them. Concerning whose wondrous operation for his seruants in these hard distresses, three memorable thinges I finde in History to be noted.

The one concerning the siege of Sanser, which City being terribly battered and raysed with gunshot of great Cannons, & field pieces, hauing at one siege no lesse then iij. thousand bullets and gunstones flying vppon them, wherwith the cristes of their helmets were pierced, their sleeues, their hose, their hattes pierced, theyr weapons in their handes broken, the walles shaken, theyr houses rent downe, yet not one person slayne nor wounded with all this, saue onely at the first a certeine mayden with the blast of the shot flying by her was stroken downe & died.

The 2. thing to be noted is this, that in the same City during all the time of the siege, which lasted 7. Monethes and halfe, for all the ordinaunce, and battering pieces discharged agaynst them, which are numbred to 6. thousand not so much as xxv. persons in all were slayne.

The third example no lesse memorable was at Rochell: Whereas the poorer sort began to lacke corne & victuall, there was sent to them euery day in the Riuer (by the hand of the Lord no doubt) a great multitude of fishe (called surdones) which the poorer people did vse in stead of bread. Which fish the same day as the siege brake vppe, departed, and came no more. Testifyed by them, whiche were present there in Rochell all the time.

What number was lost on both sides, during all this 7. monethes warre, it is not certeinely knowne. Of the kinges Campe what number was slayne, by this it may be coniectured, that 132. of theyr Captaynes were killed & slayne, of whom the chiefest was Dukedamoule.

To close vp this tragicall story, concerning the breaking vp of this 7. Monethes siege, thus it fell out, that shortly after the seuenth assaulte geuen agaynst Rochell, which was an. 1573. about the moneth of Iune, worde came to the Campe, that Duke Andius the kinges brother, was proclaymed king of Polonie. Wherat great ioy was in the Campe. By occasion whereof, the new king more willing to haue peace, entred talke with thē of Rochell, who as he shewed himselfe to them not vngentle, so found he thē again, to him not vnconformable. Whervpon a certeine agreemēt pacificatory was concluded betwene them, vpon conditions. Which agrement the new Polone king eftsoones preferred to the Frenche King hys Brother not without some sute and intercession to haue it ratified. The king also himselfe partly being weary of these chargeable warres, was the more willing to assent therunto. And thus at length, through the Lordes great worke, the kinges royal consent vnder forme of an Edict, was sette downe in writing, and confirmed by the king, conteining 25. Articles. In which also wer included certeine other Cittyes of the Protestantes, graunting to them benefit of peace and liberty of religion. This edicte or mandate sent downe from the king by his Heralde at armes, Bironius in the kinges name caused to be solemnely proclaymed at Rochell. an. 1573. the x. day of Iune.

The yeare next folowing. 1574. for two thinges seemeth fatall and famous, for the death first of Charles the 9. the french king, also most of all for the death of Charles Cardinall of Lorayne, brother to Guise. Of the maner of the Cardinals death I finde litle mentiō in stories. Touching the kinges death although Ric. Dinothus sayth nothing, for feare belike, because he being a french man, hys name is expressed and known: but an other story (whom the sayd Dinothus doth followe) bearing no name, sayeth thus, that he dyed the xxv. day of May, vpon Whitson euen, being of the age of 25. yeares: and addeth more, profluuio sanguinis illum laborasse certū est. Certayne it is that his sickenes came of bleeding. And sayth further: Cōstans fert fama, illum dum e varijs corporis partibus sanguis emanaret, in lecto sæpe volutatum, inter horribilium blasphemiarū diras, tantā sanguinis vim proiecisse, vt paucas post horas mortuus fuerit. That is. The constant report so goeth, that his bloud gushing out by diuers partes of his body, he tossing in his bedde, and casting out many horrible blasphemies, layed vpon pillowes with his heeles vpward, and head downeward, voyded so much bloud at his mouth, that in few houres he dyed. Which story if it be true, as is recorded and testified, may be a spectable and example to all persecuting kinges and Princes polluted with the bloud of Christian Martyrs. And thus muche briefely touching the late terrible persecution in Fraunce.

Taken from "A discourse of the bloudy Massaker in Fraunce" in the 1583 edition of Actes and Monuments. Available online at http://www.johnfoxe.org/

Marguerite de Valois

From The Memoirs of Marguerite de Valois,

LETTER V.

The Massacre of St. Bartholomew's Day.

King Charles, a prince of great prudence, always paying a particular deference to his mother, and being much attached to the Catholic

religion, now convinced of the intentions of the Huguenots, adopted a sudden resolution of following his mother's counsel, and putting himself under the safeguard of the Catholics. It was not, however, without extreme regret that he found he had it not in his power to save Teligny, La Noue, and M. de La Rochefoucauld.

He went to the apartments of the Queen his mother, and sending for M. de Guise and all the Princes and Catholic officers, the "Massacre of St. Bartholomew" was that night resolved upon.

Immediately every hand was at work; chains were drawn across the streets, the alarm-bells were sounded, and every man repaired to his post, according to the orders he had received, whether it was to attack the Admiral's quarters, or those of the other Huguenots. M. de Guise hastened to the Admiral's, and Besme, a gentleman in the service of the former, a German by birth, forced into his chamber, and having slain him with a dagger, threw his body out of a window to his master.

I was perfectly ignorant of what was going forward. I observed every one to be in motion: the Huguenots, driven to despair by the attack upon the Admiral's life, and the Guises, fearing they should not have justice done them, whispering all they met in the ear.

The Huguenots were suspicious of me because I was a Catholic, and the Catholics because I was married to the King of Navarre, who was a

Huguenot. This being the case, no one spoke a syllable of the matter to me.

At night, when I went into the bedchamber of the Queen my mother, I placed myself on a coffer, next my sister Lorraine, who, I could not but remark, appeared greatly cast down. The Queen my mother was in conversation with some one, but, as soon as she espied me, she bade me go to bed. As I was taking leave, my sister seized me by the hand and stopped me, at the same time shedding a flood of tears: "For the love of God," cried she, "do not stir out of this chamber!" I was greatly alarmed at this exclamation; perceiving which, the Queen my mother called my sister to her, and chid her very severely. My sister replied it was sending me away to be sacrificed; for, if any discovery should be made, I should be the first victim of their revenge. The Queen my mother made answer that, if it pleased God, I should receive no hurt, but it was necessary I should go, to prevent the suspicion that might arise from my staying.

I perceived there was something on foot which I was not to know, but what it was I could not make out from anything they said.

The Queen again bade me go to bed in a peremptory tone. My sister wished me a good night, her tears flowing apace, but she did not dare to say a word more; and I left the bedchamber more dead than alive.

As soon as I reached my own closet, I threw myself upon my knees and prayed to God to take me into his protection and save me; but from whom or what, I was ignorant. Hereupon the King my husband, who was already in bed, sent for me. I went to him, and found the bed surrounded by thirty or forty Huguenots, who were entirely unknown to me; for I had been then but a very short time married. Their whole discourse, during the night, was upon what had happened to the Admiral, and they all came to a resolution of the next day demanding justice of the King against M. de Guise; and, if it was refused, to take it themselves.

For my part, I was unable to sleep a wink the whole night, for thinking of my sister's tears and distress, which had greatly alarmed me, although I had not the least knowledge of the real cause. As soon as day broke, the King my husband said he would rise and play at tennis until King Charles was risen, when he would go to him immediately and demand justice. He left the bedchamber, and all his gentlemen followed.

As soon as I beheld it was broad day, I apprehended all the danger my sister had spoken of was over; and being inclined to sleep, I bade my nurse make the door fast, and I applied myself to take some repose. In about an hour I was awakened by a violent noise at the door, made with both hands and feet, and a voice calling out, "Navarre! Navarre!" My nurse, supposing the King my husband to be at the door, hastened to open it, when a gentleman, named M. de Teian, ran in, and threw himself immediately upon my bed. He had received a wound in his arm from a sword, and another by a pike, and was then pursued by four archers, who followed him into the bedchamber. Perceiving these last, I jumped out of bed, and the poor gentleman after me, holding me fast by the waist. I did not then know him; neither was I sure that he came to do me no harm, or whether the archers were in pursuit of him or me. In this situation I screamed aloud, and he cried out likewise, for our fright was mutual. At length, by God's providence, M. de Nangay, captain of the guard, came into the bed-chamber, and, seeing me thus surrounded, though he could not help pitying me, he was scarcely able to refrain from laughter. However, he reprimanded the archers very severely for their indiscretion, and drove them out of the chamber. At my request he granted the poor gentleman his life, and I had him put to bed in my closet, caused his wounds to be dressed, and did not suffer him to quit my apartment until he was perfectly cured. I changed my shift, because it was stained with the blood of this man, and, whilst I was doing so,

De Nangay gave me an account of the transactions of the foregoing night, assuring me that the King my husband was safe, and actually at that moment in the King's bedchamber. He made me muffle myself up in a cloak, and conducted me to the apartment of my sister, Madame de Lorraine, whither I arrived more than half dead. As we passed through the antechamber, all the doors of which were wide open, a gentleman of the name of Bourse, pursued by archers, was run through the body with a pike, and fell dead at my feet. As if I had been killed by the same stroke, I fell, and was caught by M. de Nangay before I reached the ground. As soon as I recovered from this fainting-fit, I went into my sister's bedchamber, and was immediately followed by M. de Mioflano, first gentleman to the King my husband, and Armagnac, his first valet de chambre, who both came to beg me to save their lives. I went and threw myself on my knees before the King and the Queen my mother, and obtained the lives of both of them.

Five or six days afterwards, those who were engaged in this plot, considering that it was incomplete whilst the King my husband and the

Prince de Conde remained alive, as their design was not only to dispose of the Huguenots, but of the Princes of the blood likewise; and knowing that no attempt could be made on my husband whilst I continued to be his wife, devised a scheme which they suggested to the Queen my mother for divorcing me from him. Accordingly, one holiday, when I waited upon her to chapel, she charged me to declare to her, upon my oath, whether I believed my husband to be like other men. "Because," said she, "if he is not, I can easily procure you a divorce from him." I begged her to believe that I was not sufficiently competent to answer such a question, and could only reply, as the Roman lady did to her husband, when he chid her for not informing him of his stinking breath, that, never having approached any other man near enough to know a difference, she thought all men had been alike in that respect. "But," said I, "Madame, since you have put the question to me, I can only declare I am content to remain as I am;" and this I said because I suspected the design of separating me from my husband was in order to work some mischief against him.

Taken from Memoirs of Marguerite de Valois, queen of France, wife of Henri IV; of Madame de Pompadour of the court of Louis XV; and of Catherine de Medici, queen of France, wife of Henri II; with a special introduction and illustrations (1910), p. 39. Available to read online at https://archive.org/

By the two eye witness accounts this was a plot against leading Huguenots, not meant as the horrible massacre across Paris and France, to exterminate everyone. Horrible as this was Foxe was not a witness and is biased. His account is therefore exaggerated. The numbers are also said now to be much lower and that the original orders got out of control by blood thirsty mobs. Nevertheless it was a horrible, telling and great stain on human history, a massacre of people for political or religious reasons, guests at a wedding, used in order to get rid of people a government saw as a problem. It was a dreadful event, the spilling of innocent blood.