Plough Monday was the first Monday after 6th January and was the day on which things would return to normal after the Twelve Days of Christmas and people would return to work. It was also the first day of the new agricultural year and 16th century poet and farmer Thomas Tusser wrote:

Plough Monday, next after that Twelfth tide is past

Bids out with the plough, the worst husband is last.

Ronald Hutton, in his book Stations of the Sun, writes of how there are records from the 15th century of ploughs being dragged around the streets "while money was collected behind it for parish funds" and that this money might be spent on the "upkeep" of plough lights, which were candles that were kept burning in church at this time to bring the Lord's blessing on those working in the fields. Steve Roud, in The English Year writes of how there was often a 'common' or 'town' plough that was loaned out to locals who could not afford to buy their own and that this would be kept at the parish church. Roud notes: "its presence presumably gave the opportunity for services based on blessing the plough and praying for success in the coming year".

The Reformation put an end to the practice of plough lights, because the lighting of these candles to bring a blessing was seen as superstitious, but the practice of processing around towns and villages with the plough continued. In his 19th century book The Every Day Book, William Hone wrote of the Plough Monday traditions that had survived to his time:

In some parts of the country, and especially in the north, they draw the plough in procession to the doors of the villagers and townspeople. Long ropes are attached to it, and thirty or forty men, stripped to their clean white shirts, but protected from the weather by waistecoats beneath, drag it along. Their arms and shoulders are decorated with gay-coloured ribbons, tied in large knots and bows, and their hats are smartened in the same way. They are usually accompanied by an old woman, or a boy dressed up to represent one; she is gaily bedizened, and called the Bessy. Sometimes the sport is assisted by a humorous countryman to represent a fool. He is covered with ribbons, and attired in skins, with a depending tail, and carries a box to collect money from the spectators. They are attended by music, and Morris-dancers when they can be got; but there is always a sportive dance with a few lasses in all their finery, and a superabundance or ribbons. When this merriment is well managed, it is very pleasing. The money collected is spent at night in conviviality [...]

[...]Then Plough Monday reminded them of their business, and on the morning of that day, the men and maids strove who should show their readiness to commence the labours of the years, by rising the earliest. If the plough-man could get his whip, his plough-staff, hatched, or any field implement, by the fireside, before the maid could get her kettle on, she lost her Shrove-tide c*ck to the men. Thus did our forefathers strive to allure youth to their duty, and provided them innocent mirth as well as labour. On Plough Monday night the farmer gave them a good supper and strong ale. In some places, where the ploughman went to work on Plough Monday, if, on his return at night, he came with his whip to the kitchen-hatch, and cried “c*ck on the dunghill,” he gained a c*ck for Shrove Tuesday.

You can find out more about Plough Monday traditions, which included dancing and the Plough Play in "Plough Monday and molly dancing", a BBC Radio 4 Making History programme at http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/making_history/makhist10_prog12d.shtml

Notes and Sources

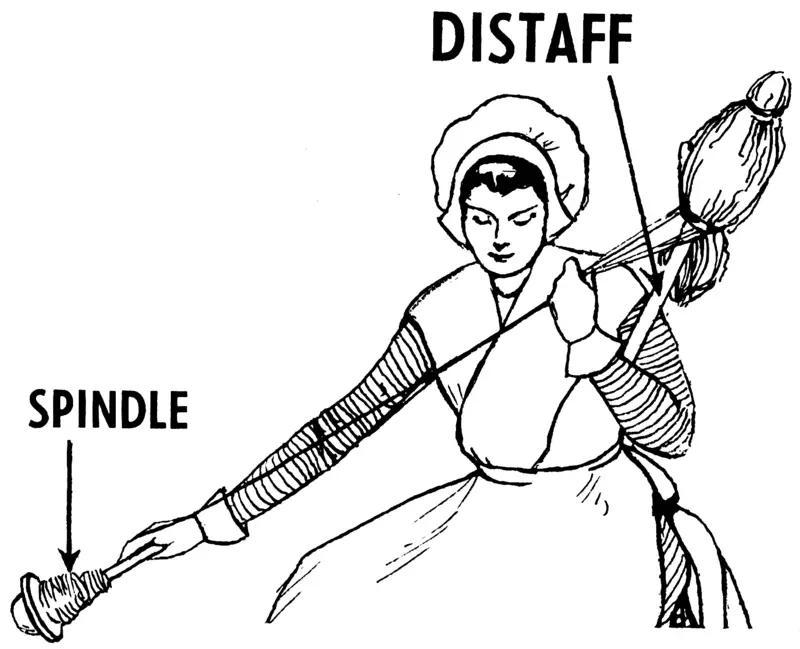

Image: Plough Monday, from George Walker's The Costumes of Yorkshire, 1814.

- Roud, Steve (2006) The English Year, p.19-21.

- Hutton, Ronald (2001) The Stations Of The Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain

- Hone, William (1825) The Every-Day Book, or, The Guide to the Year, Volume 1, p72. This can be read at http://www.hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com/Text/Hone/plough_monday.htm or Google Books

- Tudor Life magazine, January 2015, part of this article is an excerpt from my January Feast Days article in the magazine.

Leave a Reply