Anne Cooke was born the second daughter (and sixth child) of Anthony Cooke; noted tutor to King Edward VI. As the patriarch of the Cooke household, Anthony was renowned for his progressive attitude towards female education. Befitting his position, Cooke earned a distinguished reputation as England’s pre-eminent humanist scholar, alongside figures such as Sir Thomas More. Similarly, he chose to train his daughters in the same classical curriculum that he offered his four sons. (The family had four sons and five daughters) Contemporary academics, such as Dr Katherine Mair, argue that the Cooke sons have failed to remain relevant in twenty-first century historiography, in contrast to the impeccably educated Cooke daughters; women noted for their erudition and learnedness. Anne and her sisters excelled academically, in similarity to Thomas More’s daughter, Margaret, and shared a variety of scholarly interests. These included: Latin, Greek and translations. The women effectively violated the expected standards of sixteenth-century femininity by engaging in independent religious debate and writing. In terms of this article, it will intend to discuss several themes regarding Anne’s life, including her epistolary pursuits, religion, and general life.

Anne Cooke was born the second daughter (and sixth child) of Anthony Cooke; noted tutor to King Edward VI. As the patriarch of the Cooke household, Anthony was renowned for his progressive attitude towards female education. Befitting his position, Cooke earned a distinguished reputation as England’s pre-eminent humanist scholar, alongside figures such as Sir Thomas More. Similarly, he chose to train his daughters in the same classical curriculum that he offered his four sons. (The family had four sons and five daughters) Contemporary academics, such as Dr Katherine Mair, argue that the Cooke sons have failed to remain relevant in twenty-first century historiography, in contrast to the impeccably educated Cooke daughters; women noted for their erudition and learnedness. Anne and her sisters excelled academically, in similarity to Thomas More’s daughter, Margaret, and shared a variety of scholarly interests. These included: Latin, Greek and translations. The women effectively violated the expected standards of sixteenth-century femininity by engaging in independent religious debate and writing. In terms of this article, it will intend to discuss several themes regarding Anne’s life, including her epistolary pursuits, religion, and general life.

Anne was born in the English county of Essex to a high-status, ambitious family; making marriage negotiations a priority for her. Her sisters, in similarity to Anne, made good marriages by sixteenth-century standards. During this period, the institution of marriage was a convenient means of creating bonds of kinship and securing wealth; specifically when marrying off the female offspring of noble families. Anne’s sister, Mildred, married Sir William Cecil, future secretary to Queen Elizabeth I, in 1545. The future Lady Cecil would reap the benefits of such an alliance, becoming one of the Elizabethan court’s foremost ladies and gaining a reputation as a pious, intelligent woman. Her other sisters made equally successful matches: Catherine to politician Sir Henry Killigrew, Elizabeth to translator Sir Thomas Hoby, and Margaret to politician Sir Ralph Rowlett.

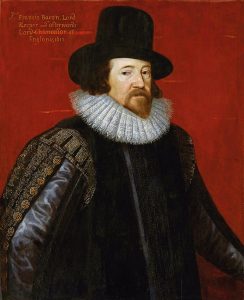

Early modern marriage was not based on the modern concept of love-matching and shared interests; rather, it proposed securing wealth, dynasty and the promotion of family interests as ideal purposes for matrimony. Anne herself married Sir Nicholas Bacon in 1553, a member of parliament who would later become Lord Keeper of the Great Seal under Elizabeth I. Additionally, he was a friend and political ally of Lady Cecil’s husband, William. This sense of kinship, and their sheer number of siblings, both male and female, ensured the Cooke family’s pre-eminent position in society. Through connections, networking and position, the family was able to rise in status, wealth and notability throughout the Elizabethan period. Lord and Lady Bacon had a comfortable marriage, and the union was successful. It produced two children: Anthony in 1558, and Francis in 1561. Previous to her marriage, Anne Cooke worked in the household of Queen Mary I, as a gentlewoman of the privy chamber. While the former was renowned for her reformist zeal in terms of theology, both mistress and queen reportedly ignored this minor difference and engaged in an amicable relationship. To support this, Anne lobbied the queen for her support in pardoning her brother-in-law, Lord Cecil. Cecil had signed the former King Edward’s ‘devise for the succession’ that effectively nominated Lady Jane Grey as his successor.

Lady Bacon has also been posthumously remembered for her letter-writing, piety and education. As Dr Gemma Allen, an expert on the Cooke women, has argued, Lady Bacon was one of the pivotal female figures, alongside Lady Lisle in Calais, who utilised the art of letter-writing for her own benefit. Her letters, primarily to her son Anthony Bacon, have become a subject of fascination and historical analysis for academics. To quickly preface, Anne’s education ensured that she was able to become steadfast in competent hand-writing - a result of numerous translations and literacy practice. Her letters vary in their content and style, however, the ones addressed to her children essentially remain concerned with their well-being, spirituality and obedience. As historian Dr Mair has argued, their contents represent the social and cultural obligations expected of a zealous Protestant mother to her son; Anthony was expected to reply with affection and obedience. What is poignant is that in the majority of her son’s responses, he signs off with unwavering, subordinate salutations. For example, ‘your most humble and obedient sonn’, or, ‘my most humble duty remembered’. The distinction between status and rank, mother and son, are evident. In contrast, his mother’s letters are exceedingly less affectionate, rather, she addresses him bluntly: ‘to my sonn Mr Anthony Bacon’. Anthony, more formerly, addresses his mother as ‘to the honourable his very goode ladie and mother the Lady Anne Bacon Widdowe’. These differences demonstrate the evident juxtapositional standards in familial early modern letter-writing: Anne being the dominant writer and Anthony being the subordinate recipient. Lady Bacon’s wealth of letters are not only concerned with the pastoral and spiritual well-being of her children; indeed, she utilised them to manage her household and administrative affairs. Similarly, she facilitated the written word to cement ties of kinship and to voice her opinion in an age that intended to suppress women’s personal and individual thoughts.

While letter-writing was intrinsic to Lady Bacon’s academic nature, her fervency for advocating religious reform within the Church of England requires particular attention. Anne’s ‘claim to fame’ was corroborated by her contribution to translations, particularly in 1564 for her translation of the Bishop of Salisbury’s Apologie of the Church of England. This Latin to English piece was well received by Archbishop Matthew Parker, who arranged for the manuscript to be published. The Bishop of Salisbury’s Apologie essentially underpins the Church of England’s position against Roman Catholicism, alongside differentiating between the two styles of faith. Lady Bacon’s translation into English enabled the piece to be read across a vast number of literate audiences; a significant grievance of the Protestant manifesto in England. Lady Bacon evidently viewed this as her spiritual mission, in advancing the true interpretation of the gospels to the masses. While this was an impressive effort from Anne, her introduction into feminine academia originated before both the Elizabethan and the Marian periods; in 1548 she translated the Italian Bernardino Chino’s sermons. Under the authority of the Edwardian regime, Evangelicalism was able to be more freely expressed than when under the pseudo-conservative Henrician regime; a period that wavered between tradition and reform. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, Anne’s father was tutor to King Edward, which provided a climate of Protestant tolerance and advocacy. Anne Cooke evidently capitalised on this security of religious expression, and put forward her debut translation under a sympathetic government.

Lady Bacon’s sister, Lady Hoby, had an equally successful career in terms of academia. She translated a way of reconciliations touching the true nature and substance of the body and blood of Christ in the Sacrament, from the French. It was composed in tomb inscriptions in Greek, Latin and English. In similarity to her sisters, Lady Hoby was a deeply religious Protestant, whose interpretation of Biblical scripture ventured into Puritanism; a stricter, fundamentalist view of the Bible and the world. An example of her fervency was her opposition to live theatre, as a result of its physical, bodily expressions that were deemed ‘ungodly’ and ‘sinful’.

Lady Bacon died sometime after 27th August 1610. While her exact date of death cannot be stated, during her final days she wrote a letter to her friend, Sir Michael Hicks, inviting him to her funeral; evidently, she was aware of her imminent death. Lady Bacon was around the age of eighty-two when she died and was entombed in St Michael’s Church in St Albans, Hertfordshire. Her youngest son, Sir Francis Bacon, was buried alongside his mother upon his death in 1626.

by Alexander Taylor

Thank you for this interesting information, Claire! I sometimes wonder how much women like Anne Bacon neé Cook would have achieved if they had lived in modern times. Maybe Anne or one of her sisters would have been Prime Minister of the UK.

My next email to my 19 year old son:

“To My Son, Mr. J A Armbruster….

…..I trust that you will write back soon as part of your filial duties to your Honourable and Very Goode Mother, for you are my humble and obedient servant.”

Love,

Mom

My 13 x great, great Aunts are Anne and Lady Elizabeth Cooke Hoby through the Cooke family… so fascinating how clever they were. I too liked writing as a child and became a Secretary as a teenager.