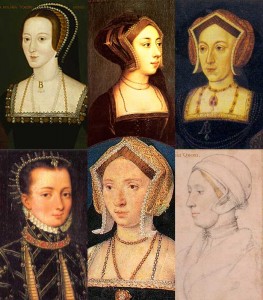

Every aspect of Anne Boleyn's life is controversial. Her birth date, her personality, her relationship with Henry VIII, whether she was guilty of the crimes attributed to her – all of these, and more, arouse fierce debate. But it is Anne's physical appearance that is perhaps the most lingering and heated of controversies about her. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the news this week, when it was declared that the Nidd Hall portrait of Anne (above, right) is in fact a realistic depiction of Anne, because of its close match to the 1534 medal bearing a defaced Anne alongside her motto ‘The Most Happi’. Yet the researchers involved in this have warned that their recent findings have been misinterpreted by the press. The overall results from their research remain incomplete. So much, then, for discovering what Anne Boleyn ‘really’ looked like.

Every aspect of Anne Boleyn's life is controversial. Her birth date, her personality, her relationship with Henry VIII, whether she was guilty of the crimes attributed to her – all of these, and more, arouse fierce debate. But it is Anne's physical appearance that is perhaps the most lingering and heated of controversies about her. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the news this week, when it was declared that the Nidd Hall portrait of Anne (above, right) is in fact a realistic depiction of Anne, because of its close match to the 1534 medal bearing a defaced Anne alongside her motto ‘The Most Happi’. Yet the researchers involved in this have warned that their recent findings have been misinterpreted by the press. The overall results from their research remain incomplete. So much, then, for discovering what Anne Boleyn ‘really’ looked like.

As Susan Bordo notes, ‘beyond the dark hair and eyes, the olive skin, the small moles, and the likelihood of a tiny extra nail on her little finger, we know very little with certainty about what Anne looked like’, in no small part because of the campaign of destruction waged against her by her husband after her death, in which portraits of her were destroyed. Contemporary descriptions of Anne’s appearance, moreover, were rarely objective and were influenced by religious, political and cultural mores, viewing her either as a paradigm of religious virtue or as the incarnation of the Devil. Nicholas Sander, a hostile Jesuit priest writing in the reign of Anne's daughter Elizabeth I, clearly subscribed to the latter view:

Anne Boleyn was rather tall of stature, with black hair and an oval face of sallow complexion, as if troubled with jaundice. She had a projecting tooth under the upper lip, and on her right hand, six fingers. There was a large wen under her chin, and therefore to hide its ugliness, she wore a high dress covering her throat. In this she was followed by the ladies of court, who also wore high dresses, having before been in the habit of leaving their necks and upper portion of their persons uncovered. She was handsome to look at, with a pretty mouth.

Modern historians firmly discount Sander's prejudiced, malignant portrayal of Anne's appearance, noting the contradictions (she was ‘handsome’, ‘with a pretty mouth’, despite her glaring deformities). Only six years of age when Anne was executed, Sander never saw her in the flesh, meaning that his account is probably little more than character assassination, informed by his own fantasies. Moreover, Sander was influenced by the belief that the exterior of a person reflected their interior: regarding Anne as responsible for England's schism, he characterised her as deformed, witch-like, the very embodiment of evil. As historians note, Anne would never have been invited to court, much less never have captivated Henry VIII, had she been as grossly deformed as Sander claimed.

George Wyatt, the grandson of the famed Tudor poet Thomas Wyatt (who may, perhaps, have admired Anne), wrote an account of Anne's life to counter Sander's malicious claims. He admitted:

There was found, indeed, upon the side of her nail, upon one of her fingers some little show of a nail, which yet was so small, by the report of those that have seen her, as the work master seemed to leave it an occasion of greater grace to her hand, which, with the tip of one of her other fingers might be, and was usually by her hidden without any blemish to it. Likewise there were said to be upon some parts of her body, certain small moles incident to the clearest complexions.

Perhaps, then, Anne did have a slight growth on one of her fingers, but it hardly amounted to a sixth finger. Moreover, even this has been questioned. Retha Warnicke thoughtfully noted that sixteenth-century individuals were horrified by even minor deformities, explaining that Henry VIII himself refused to marry Renee of France upon hearing rumours of her limp and deformed appearance. It remains questionable, then, whether Anne did have ‘some little show of a nail’, but it can safely be asserted that she did not have a sixth finger.

The fullest description we have of Anne Boleyn’s appearance comes from the Venetian diplomat, writing in 1528 when she was perhaps only twenty-one years of age (if one accepts that Anne was born in 1507):

Not one of the handsomest women in the world; she is of middling stature, swarthy complexion, long neck, wide mouth, a bosom not much raised and eyes which are black and beautiful.

Contemporaries were united in their belief that Anne's dark eyes were her most striking feature. Lancelot de Carles, a member of the French embassy who wrote an account of Anne's downfall in 1536, referred to her ‘eyes, which she well knew how to use. In truth such was their power that many a man paid his allegiance’. He further described Anne as ‘beautiful, with an elegant figure’, and as being ‘of fearful beauty’ just days before her execution. Anne's grace was also noted by de Carles, writing: ‘She became so graceful that you would never have taken her for an Englishwoman, but for a Frenchwoman born’. Anne was known to have been dark. Simon Grynee, professor of Greek at Basle, stated that her complexion was ‘rather dark’, while Thomas Wyatt’s ‘Brunet’ in his poetry could perhaps refer to Anne. Cardinal Wolsey disparagingly called her ‘the night crow’.

Observers mostly agreed that Anne was not the most beautiful of women at court. One individual, writing in Elizabeth's reign, admitted: ‘albeit in beauty she was to many inferior, but for behaviours, manners, attire and tongue she excelled them all, for she had been brought up in France’. As we have seen, the Venetian diplomat stressed that she was not the ‘handsomest’ at court. Indeed, Anne was admired not so much for her physical appearance, as for ‘her excellent grace and behaviour’.

In summary, Anne Boleyn may not have been conventionally beautiful. She had beautiful dark eyes, was of medium height, with a dark complexion, and small breasts. Her hair colour has incited particular controversy. Sander is the only writer to characterise her as black-haired, probably to fit in with his conception of her as a witch. That Anne was brunette seems safe to say, going by Wyatt’s description and Wolsey’s allusion to her as ‘the night crow’. Yet, as Bordo concludes, ‘raven-haired Anne – Sander aside – is largely a twentieth-century invention’, explaining that Anne could well have been auburn or red-haired. We simply cannot rely on Anne’s portraiture to establish what she looked like, for Tudor portraits do not provide accurate depictions of their sitters' physical appearances. As Lacey Baldwin Smith noted, ‘Tudor portraits bear about as much resemblance to their subjects as elephants to prunes’. It was not, perhaps, Anne's beauty that captivated Henry VIII. Rather, as Bordo explains:

Anne… seems to have had that elusive quality – “style” – which can never be quantified or permanently attached to specific body parts, hair color, or facial features, and which can transform a flat chest into a gracefully unencumbered torso and a birthmark into a beauty spot… Style defies convention and calls the shots on what is considered beautiful…

The aim of this article is to question why Anne Boleyn’s physical appearance matters. Why does it seem a prerequisite of modern cultural works, including film and TV portrayals, to depict Anne as stunningly beautiful, an exquisite woman who effortlessly outshone all other women in her looks? To do so is to distort her history and to mock her life for what it was. Anne clearly was not a great beauty, by the standards of her day. Rather, it was her charm, her vivacity, her eloquence, her considerable talents, her intelligence and, perhaps above all, her opinions, which captivated not only Henry VIII but other admirers at court. Anne epitomised style and elegance, she embodied grace and charm. Whether she was black-haired, auburn, or chestnut-haired; whether her eyes were black, brown or somewhere-in-between; whether she was tall, short, slender or plump; it really doesn’t matter. Anne Boleyn contributed to changing England's history forever. She was a prime mover in the English Reformation, was involved in the English Renaissance, and was the mother of Elizabeth I, who many regard as England's greatest monarch. Surely we should be admiring her achievements and celebrating her talents, rather than concerning ourselves with the trivial matter of her appearance. Perhaps now we can finally come to the realisation that we will never know what Anne ‘really’ looked like. Perhaps, then, we can realise that it really doesn't matter.

See also Claire's article Anne Boleyn, Nanny McPhee and Nicholas Sander over on The Anne Boleyn Files.

Notes and Sources

- Sander, Nicholas (1585) Rise and Growth of the Anglican Schism

- Bordo, Susan (2013) The Creation of Anne Boleyn: A New Look at England’s Most Notorious Queen

- Wyatt, George, The Life of Anne Boleigne, in Cavendish, George, The Life of Cardinal Wolsey

- Warnicke, Retha (1991) The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn: Family Politics at the Court of Henry VIII

- Calendar of State Papers and Manuscripts, Venice, Vol. 4 (1527-1533)

- de Carles, Lancelot, in Ascoli, George, La Grand-Bretagne Devant L’Opinion Francaise, 1927

Conor Byrne, author of Katherine Howard: A New History is a British undergraduate studying History at the University of Exeter. Conor has been fascinated by the Tudors, medieval and early modern history from the age of eleven, particularly the lives of European kings and queens. His research into Katherine Howard, fifth consort of Henry VIII of England, began in 2011-12, and his first extended essay on her, related to the subject of her downfall in 1541-2, was written for an Oxford University competition. Since then Conor has embarked on a full-length study of qyeen Katharine's career, encompassing original research and drawing on extended reading into sixteenth-century gender, sexuality and honour. Some of the conclusions reached are controversial and likely to spark considerable debate, but Conor hopes for a thorough reassessment of Katherine Howard's life.

Conor runs a historical blog which explores a diverse range of historical topics and issues. He is also interested in modern European, Russian, and African history, and, more broadly, researches the lives of medieval queens, including current research into the defamed ‘she-wolf’ bride of Edward II, Isabella of France.

If her appearance doesn’t matter as written actually in the article…why write the article? Just curious.

I can’t really comment for Conor but I suspect because of the fact that newspapers from all over the world were reporting on the Nidd Hall portrait and the facial recognition software last week. Although the news reports were false, it went viral and was causing so many discussions about Anne’s appearance.

Ps.Conor didn’t say her appearance doesn’t matter, he said, or to be exact, he wrote, “the aim of this article is to question why Anne Boleyn’s physical appearance matters.”

Because it’s been written so many times that it was her” beauty “ that caught the King’s eye when he actually met her when he met her sister Mary that became his mistress first. Ann was very intelligent and knew how to use it wisely ( so I’ve read) but say she was admired because of her “ brain and opinions “ as a woman at that time would have most likely not been well received. Especially when you as King are breaking all the rules to marry her. She historically has received a very bad wrap. Henry was the bad guy. But hey he was the “King” that thought he was God and treated that way or you died!

I’m sorry but she was a hussy. She cared little for the fact he was married. She cared even littler for the fact that her older, married sister had been made to bed him to further her uncle and fathers ambitions, and was now pregnant with his child. She used her body as a tool, no different than a prostitute. I really feel she earned her reputation, it is not at all unfair. I say that assuming that most of the rumors about her unfaithfulness during the marriage were made up by the privy chamber to alleviate Henry of his wife now that he had moved on and become tired of her.

That’s certainly the Anne Boleyn of fiction, but that’s not what history tells us at all:

1) When Henry VIII began courting her, she rebuffed him, left his letters unanswered and even left court for Hever to get away. Thomas Wyatt depicts her as a hind hunted down and made the king’s. While that may be an exaggeration, Anne was not in a position of power. The king was God’s anointed sovereign and her family’s careers and finances were in his hands. Plus the king would have told her that his canon lawyers had advised him that his marriage was invalid and had always been so.

2) We don’t know when Mary Boleyn slept with the king. We don’t know anything about it, when it happened, how often, whether it was just once, only that it happened. If the king used the same MO as he did with Bessie Blount, then she slept with Mary BEFORE she was married, probably while Bessie was pregnant in 1519, and then arranged a marriage for Mary. There is absolutely no evidence that either of Mary’s children, born in 1524 and 1526 were the king’s.

3) There appears to have been distance and division between the Boleyns and Mary, possibly due to unhappiness with her getting involved with the king. We know from Chapuys that Thomas Boleyn was not happy with Anne being involved with the king and that her uncle wasn’t either. Anne complained about his lack of support.

4) What is your evidence for Anne using her body as a tool like a prostitute?

5) There is no evidence that members of the King’s privy chamber, members of whom were executed in May 1536, made up any rumours about Anne.

I just don’t understand your comment and what it’s based on.

1. It has always been clear Anne USED the MARRIED King to further her family’s ambitions. She didn’t have to marry him. Come on, she knew he was married she had no business enticing him then marrying him.

2. Where there is smoke there is fire, he probably did bed Anne’s older sister who he clearly preferred over Anne who was considered plain by pretty much everyone except the desperate King.

3. You don’t go around with married men and getting them to LEAVE their wife and kids, you walk away it isn’t hard ! A prostitute would do this very thing however though of course we have no proof of her selling her body except for her “marriage” to the King.

4. It says a lot when the guy who supposedly left his legitimate wife and child for crosses you out in every way possible in portraits emblems even disinheriting their child together Elizabeth I. Even while he reinstated his offspring he NEVER forgave Anne. Funny he never tore down, burned or desecrated his true wife’s portraits. We know what Queen Catherine of Aragon looked like as he left her portraits alone and he certainly never DARED put her head on the block to be cut off and made sure his daughter was in line for the crown ahead of Elizabeth. Why? I would guess 1 part regret the rest true love for the woman he loved first and most. So DEEP was his regret for leaving the Catholic faith he died a Catholic and was given Catholic last rites by a CATHOLIC priest. Indeed it was said he blamed Anne for turning him away from the Catholic Church.

Lastly I believe Anne looked like the Holbein portrait. It was said he did ALL of his portraits using a camera obscura. As someone who is not only a historian but also an artist I would agree. it was VERY popular at the time. The Wren on her neck, appears to be present in the painting the features look right. He had yet to paint in the rest and just titled it Queen Anne Boleyn. I don’t think we need any other proofs to what she looked like, disappointing Anne fans It shows a plain Wren necked woman in contemplation.

She actually didn’t use her body as a tool, per the entire point of this article, which you seemed to have missed. Do you realize her and Henry dated for like 7 years before he could be “officially” divorced and have a legitimate heir with Anne? You think that’s using her body?

Just because Anne may have manipulated her way to the top isn’t an excuse to say she’s a wh*re. Henry was sleeping around but you don’t claim that he had the same disregard for marriage. She did what she had to to get what she wanted, she knew how to play the game. Life with the king was obviously vicious and because she knew that he was interested in her physically doesn’t mean that she didn’t care that he was married and that she behaved like a prostitute. We don’t think that she slept with him for at most 7 years, and before that Catherine of Aragon was basically put aside. I’m not defending Henry’s treatment of Catherine, that was cruel, but she was out of the picture. He was unhappy with her before he even met Anne. Being attractive to someone is nobody’s fault, and saying that she acted like a prostitute to manipulate Henry isn’t fair at all. Anne figured out how to play the game. Her taking control of a crappy situation isn’t an excuse to call her a hussy.

Taking another woman’s husband is her fault he was married who cares how long she dangled the carrot for until she got her so called prize she was guilty and will always be seen as a homewrecker. She used the King’s weakness his need of an Heir. She beat the CRAP out of her step daughter REGULARLY.

She was a wicked stepmother in every respect. She deserved her fate.

It seems to me perfectly natural to be curious about what people looked like, especially when it is a woman who has captured the interest of a king. Men are not usually indifferent to a woman’s appearance – looks matter, as every woman knows. So anne Boleyn’s looks are not irrelevent.

I think I have been misinterpreted.

I never claimed that Anne Boleyn’s looks were ‘irrelevant’. Rather, the article explained that Anne’s personality and achievements were what brought her to the throne of England. She was a pivotal player in the English Reformation, was closely involved in politics, and was interested in the Renaissance. Eric Ives has pointed out her artistic interests and pursuits.To reduce her to a pretty plaything, as occurs sometimes in popular culture, is to completely underrate and distort her history.

You were perfectly clear in your placing far greater importance to Anne Boleyn in all that she was, and she apparently was a highly intelligent and complex woman. In all that she was, not by some singular standard of beauty she captivated Henry. Of Court ‘beauties’ he could have them all. But Anne Boleyn then as women of intelligence, grace, charm and style have today, a beauty that they define.

No misunderstanding. You conveyed the idea perfectly.

Well said Conor! I’ve spent a lot of time scrutinising images of Anne Boleyn partly because of my reconstruction of the Moost Happi portrait medal, partly because like every other Anne Boleyn fan I yearn to see her face – as if we might find greater insight into her character. However, I heartily agree that our fascination with Anne’s appearance should not overshadow the evidence (small and fragmented though it is) of her strong character, wit, taste and intelligence. To obsess with her appearance is a great injustice to Anne and her legacy.

I think Jennifer, that Conor is posing the question of why her looks should matter so much when her life was so remarkable?

It has to be admitted that these days, with a fan culture around Anne, people emphasize her looks and *want* her to have been beautiful, and that is measuring her by our standards. The point is she was not considered conventionally beautiful, but her wit and charm was such that she was considered striking. That tells us quite a bit about her personality.

Oh it does matter so much so. I would definitely like to put a face to the name once and for all like I am sure others would too once and for all! 🙂

Appearance matters, down to the bone. One only has to consider Richard iii. Will Anne be subjected to such scrutiny if her body is unearthed?

My favourite picture of Anne is the John Hoskins portrait.

I think we have to remember, that what the artist sees is very different to the actual person.

The Hever portrait is the general accepted view of Anne. Facial reconstruction is ok, but again it isn’t fool proof.

Even a camera picture can be tampered with these days via photoshop.

I remember once many years ago, a skull had been found of a woman who had disappeared a few years before, and the artist reconstructed the face, of what she thought the woman would look like. Whilst she was doing that the Polic were doing their bit, and managed to track down the woman’s mother and sister, via DNA. By this time of course the artist had done her bit, when the face was revealed it was nothing like the photograph that the mother and sister had brought in. The artist tried to say that the police were wrong with their findings etc.. DNA so they did another test just to double check. Same result the skull belonged to the daughter/sister of the woman in the picture.

I don’t think we can ever really be sure what Anne looked like, but I do believe that rather than beautiful she was striking to look at, and because of the way she dressed etc, she stood out in the crowd. I must confess thought (No slapping my wrists here Claire) That Anne in a gable hood looks simply awful. It really doesn’t suit her…

I would definitely like to know what Anne looked like. I don’t want her to be beautiful but -in my opinion- just BECAUSE she achieved all these amazing things she deserves to have a face to her name.

I know what you mean Audrey. I think that’s why I felt honour-bound to restore the features of the Moost Happi medal (because I’m trained in restoration, and I could see there was still a lot of useful information left in the damaged original). I felt a duty raise attention to the evidence that we have of this remarkable woman.

Audrey:

The trouble is again that we all have our own images in our heads to what Anne looked like. If we are able to ever get a Bona Fide 100%, tried and tested, done and dusted true likeness of Anne, we would still have our own interpretation of what she looked like.

I agree mind you it would be nice to know what Anne truly looked like. I do really hate to say it, but of the 2 sisters I would say that Mary was better looking than Anne. I think that Anne looks were more Howard like in appearence, if that makes sence. We also have another question here as well, what did Katherine Howard truly look like? I have read somewhere, that K.H resembled Anne in looks, or at least had similar features. If true this kind of bears out my idea of Anne being more Howard like in appearence. Either way if we do ever manage to get a true likeness of Anne I would be happy to say, that’s Anne my freind, the woman who changed the world.

Lorna, we don’t know for sure what Katherine Howard looked like because there is no confirmed portrait of her. Yes, the Holbein miniature could depict her, but some suggest it is actually of Margaret Douglas. All we know is that Katherine was ‘diminutive’ in stature, which indicates she was less than five feet tall, and observers rated her beauty from average to dazzling.

Anne was of ‘middling height’, which means she was taller than Katherine, and probably darker than her too.

Thank you Conor. It’s just so sad that we know so little about K.H. You have of course done sterling work, in giving us a glimpse into her breif life. I tend you view K.H as a little girl thrown into the lions den, and devoured.

She tried her best to please an old stinking fat man, and it still wasn’t enough.

I don’t believe she and Culpepper had a sexual relationship. In much the same way I don’t believe the letter find in Culpepper’s belongings was entirely true. I have no proof to back this up of course. But it’s my opinion, that the letter has been cobbled together from other letters. Would love to know your opinion on this Conor?

For me, the best writers of history are able to transport the reader to the time and place so that history is seen and felt – i.e., it resonates. If historical characters have a face, then the history is more vivid. Our fascination with Anne and what she looked like is probably responsible for much of the quality research and insights historians have contributed over the last twenty years.

And, some of us are just visual people – we learn and retain more from seeing things.

Look at her daughter Elizabeth. Though Elizabeth had her father’s hair and eye color, she perhaps inherited her mother’s eye shape or nose or lips. Then compare to the alleged Anne portraits.

Elizabeth the 1st actually had the dark eyes of her mother with only the hair and skin color of her father. I believe personally that the “princess” picture of Elizabeth (she looks to be 15 or 16 years old) is exactly what Anne would have looked like. So thank you Mary for sharing that because, I too, look at Elizabeth’s portraits to see Anne.

It is all for nothing! In 2020 Channel 5 are portraying Anne Boleyn as a very dark girl indeed!

Many of the pictures done after Anne was gone have softened her features to make her look prettier. Elizabeth I was said to resemble her mother apart from her coloring. When I look at the Anne’s Nidd Hall portrait and Elizabeth’s portraits as an adult, I see a definite resemblance. The Nidd Hall portrait shows a strong face with character and a sallow skin color (Anne was said to have sallow skin coloring). I believe it is the closest to what she actually looked like, but since the artist had limitations (he was no Holbein), it isn’t the perfect portrait either. But I think it is very close to her overall appearance. The Nidd Hall picture also looks more like the face in Elizabeth’s locket ring, which depicts Anne and Elizabeth. As mentioned above, it also looks most like the “Moost Happi Medal.” Most of the portraits of Anne lack personality and do not reveal her strong personality. The Nidd Hall portrait is the exception.

It matters, so firing voice actors because they are white and voice black animation characters is all good, black people should voice black characters so in this case white people should play white actors

She was Black. Her appearance was controversial and that’s why her image has been whitewashed. The Neanderthals know no bounds to revising the story.

Whether they were building her up or tearing her down, not one contemporary writer refers to her in a way that would suggest she was a black woman. Olive skin tone does not necessarily equate to African heritage as some seem to be suggesting. She is being blackwashed right now in keeping with the “woke” times we live in.

Anne was definitely a Black woman. She was descended from a family who were related to the British Royal family, who are descendents of Kenneth Macalpine or Kenneth I of Scots, who was definitely black and was described as such. Therefore all the Royal family, Tudors included and their relatives are from aine of Moorish Kings.

Don’t ask. I am still getting over the first bit.

Weird! 🤣🤣🤣

It seems likely that Anne’s vivacity, intelligence, and fire is what caught the king’s eye. Of course she would have been good-looking as well with a good figure, but not necessarily superlatively beautiful in the conventional way. In addition, she was unmarried, presumed to be virginal, and thus marriage eligible in a way some of Henry’s lovers were not. In addition, she knew the manners of courtly love, which Henry enjoyed playing at.

This presented a problem for historians to explain Henry’s interest in her, so they focused on her beauty as the thing that entrapped him.

Regarding the suggestion of red or auburn hair, that is extremely unlikely. She likely had dark brown or black hair to go with her dark eyes and dark complexion (for an Englishwoman). Red hair comes with pale skin, and in groups where skin is routinely dark or olive, red haired people have skin several shades lighter than normal. Look up the Iraqi general with red hair, Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri.