The brief life of Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick, can be interpreted as an exercise in the harsh realpolitik of fifteenth-century England. The only son and heir of George, Duke of Clarence, Edward was born on 25 February 1475 in Warwick; his sister Margaret had been born two years previously. He was the nephew of the first Yorkist king, Edward IV, who had seized the throne from Henry VI in 1461. Edward's mother Isabel, sister of Richard III's consort Anne Neville, died when he was an infant, and his father was executed for treason in 1478. The lands of Clarence were seized by the Crown, including those belonging to his infant son. In 1481, Edward was placed in the wardship of Thomas Grey, Marquis of Dorset. He attended the coronation of his uncle Richard in 1483 and was knighted at the investiture of Richard's heir, also named Edward, at York in September. The prince died the following year and it is possible that the king considered the Earl of Warwick as his heir.

The brief life of Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick, can be interpreted as an exercise in the harsh realpolitik of fifteenth-century England. The only son and heir of George, Duke of Clarence, Edward was born on 25 February 1475 in Warwick; his sister Margaret had been born two years previously. He was the nephew of the first Yorkist king, Edward IV, who had seized the throne from Henry VI in 1461. Edward's mother Isabel, sister of Richard III's consort Anne Neville, died when he was an infant, and his father was executed for treason in 1478. The lands of Clarence were seized by the Crown, including those belonging to his infant son. In 1481, Edward was placed in the wardship of Thomas Grey, Marquis of Dorset. He attended the coronation of his uncle Richard in 1483 and was knighted at the investiture of Richard's heir, also named Edward, at York in September. The prince died the following year and it is possible that the king considered the Earl of Warwick as his heir.

During Richard III's reign, Edward resided at Sheriff Hutton in North Yorkshire in the company of his cousins John, Earl of Lincoln, and Elizabeth, later Queen of England. Christine Carpenter has indicated that the king surely favoured his nephew John as heir to the throne rather than his nephew Edward, in view of ‘the dangers of drawing attention to the fact that Edward had a better claim to the throne than Richard himself.’ However, as the son of a convicted traitor, it is improbable that Edward could have convincingly pressed his claim had he been so inclined.

Traditionally it has been speculated that the earl of Warwick was disabled, primarily because the Tudor chronicler Edward Hall later asserted that Warwick’s imprisonment ‘out of all company of men, and sight of beasts, in so much that he could not discern a goose from a capon.’ This comment, however, seems to suggest that the earl’s education was limited, rather than indicating a disability.

His imprisonment commenced in 1485 when his uncle Richard III was slain in battle at Bosworth and the throne was seized by Henry Tudor. Both the new king and his son – the future Henry VIII – demonstrated an ability to treat the House of York with calculated harshness. Henry VII ordered the removal of Edward from Sheriff Hutton to the Tower of London. The new king, however, was not secure on his throne during the early years of his rule, and disaffected Yorkists perceived the Earl of Warwick to be the rightful heir to the throne. Plots and conspiracies focused on deposing the Tudor king and replacing him with Edward. However, it was the actions of the pretender Perkin Warbeck that ultimately sealed Edward's fate. Warbeck, who pretended to be Edward IV's son, Richard, Duke of York, was incarcerated in the Tower in 1498. He was accused of plotting to escape from the Tower in the company of the earl; the latter was also thought to have plotted the deposition of the king.

In November 1499, Warbeck and Warwick were tried at Westminster. Both were found guilty of treason and Warwick was executed on 28 November at Tower Hill. The earl was buried at Bisham Abbey in Berkshire. There is no evidence to indicate that Warwick had actually conspired to effect Henry VII's deposition and death; it is more likely that the earl was removed in response to pressure exerted by Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, who were desirous of achieving a marital alliance between their daughter Katherine and Henry VII's son Arthur. According to the later testimony of Jane Dormer, Duchess of Feria, Katherine ‘applied these miseries and disasters to have specially happened for the death of Prince Edward Plantagenet, son of the Duke of Clarence, brother to King Edward the Fourth; whom (most innocent) Henry VII put to death to make the kingdom more secure to his posterity, and to induce King Ferdinand to give his daughter, this Catharine, in marriage to Prince Arthur’. In 1541, Edward’s sister Margaret was brutally executed on the orders of Henry VIII. Like her brother, there was no evidence to indicate that she was guilty of treason; rather, it seems more likely that both siblings were put to death as a means of eliminating any perceived threat posed by the house of York.

Conor Byrne is the author of Katherine Howard: A New History and Queenship in England: 1308–1485 Gender and Power in the Late Middle Ages. He is a British graduate with a degree in History from the University of Exeter. Conor has been fascinated by the Tudors, medieval and early modern history from the age of eleven, particularly the lives of European kings and queens. His research into Katherine Howard, fifth consort of Henry VIII of England, began in 2011-12, and his first extended essay on her, related to the subject of her downfall in 1541-2, was written for an Oxford University competition. Since then Conor has embarked on a full-length study of Queen Katharine's career, encompassing original research and drawing on extended reading into sixteenth-century gender, sexuality and honour. Some of the conclusions reached are controversial and likely to spark considerable debate, but Conor hopes for a thorough reassessment of Katherine Howard's life. Conor runs a historical blog which explores a diverse range of historical topics and issues. He is also interested in modern European, Russian, and African history, and, more broadly, researches the lives of medieval queens, including current research into the defamed 'she-wolf' bride of Edward II, Isabella of France.

Conor has just completed his Masters.

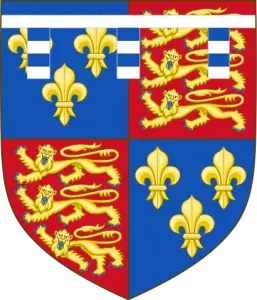

Picture: Arms of Edward Plantagenet.

Edward of Warwick is a curious young man for a couple of reasons

*Henry Tudor was terrified of a ten year old boy, who yes, had a better claim, but was banned by law. Why else would he lock him up, even if he was comfortable and more “in protective custody” from the point of view of the crown .

*There are several gaps in his story which are often filled by some curious stories that fascinated many historians for years and which feed into the tradition of the Princes in the Tower.

* Henry sacrificed him because of the demands of Spain and to secure the future of his own two sons.

*He was connected to the first so called pretender Lambert Simnel, although there is much contradictory evidence as to whether John of Lincoln really led the rebellion which ended at Stoke Field in 1487 or whether he rose in the name of another. There is also some debate as to whether the Dublin King as the true leader was known was the presumed dead Edward V or the Earl of Warwick. Henry appeared to be certain it was Warwick or at least put it about that it was Warwick he claimed to be.

*Warwick all but became forgotten until the set up with the man called Perkin Warbeck, who claimed to be Richard of England, Duke of York, second son of Edward iv and the rightful King, who Henry also had to get rid of to please Spain.

Edward was said to be an imbecile by Edward Hall, a view repeated by Leanne de Lisle in her epic on the Tudor Family without checking what is a late source for validation. Hall is only repeating the rumours about this young boy who was shut away with few visitors and who had made only one or two trips outside, which should be read as having limited education, to keep him submissive and easy to control. Besides, who knows, he might not have been able to tell the difference between a capon and goose, depending on the quality of food given to him.

There was a story that young Warwick had been smuggled out of the country just before his father made his fatal moves in 1477 and that the boy handed over from Sheriff Hutton to Henry’s agents was a double and that he had the fake Warwick in the Tower. Henry himself showed signs of doubt but he most likely did have the real York Prince and he made enough of a show at Saint Paul’s to say that he was the real thing. However, rumours persisted that this young man was not who he claimed to be. The attendance by the Earl at Richard iii coronation may have appeared to put this story to bed, but still it persisted.

Warwick was in the Tower for fourteen years, coming out once that we know of, to prove his identity and so as Henry could watch his interaction with Lincoln and Suffolk that day. That night Lincoln fled and his conspiracy was to take shape after this event. Whether the boy left on the battlefield was meant to be Warwick, a nobody exchanged for a real Prince or just a fake, has been debated, with the Irish Lords swearing the boy, meant to be Lambert, who served them wine, some years later, was not the same boy they had crowned in 1486.

For seven years a young man plagued Henry, claiming to be the son of Edward iv, Richard, Duke of York, with support from Flanders, Cornwall, Scotland and France and the Holy Roman Empire. He was eventually captured and he was either forced to make a confession or given a prepared confession which claimed he was a commoner, the son of a boatman and customs officer in Tourney in Flanders. He is known officially to history as Perkin Warbeck or Piers Osbeck, according to both earlier enquiry and two different versions of this confession. He was trouble and Henry showed he feared him. After his defeat and capture it was important to show him as a fake and now, with an alliance forming with Spain, it was important to show them as well that he now had full control of his kingdom. This meant no more rivals, no more rebellions, no more heirs, abroad or in captivity. Before the deadline of 1501 when Prince Arthur married the Spanish Infanta Katherine of Aragon somehow Warbeck (Richard of England) and Warwick had to go. The escape six months after his capture was about the time of the fire at Sheen and he may have been allowed to escape by Henry, although its not likely that the fire was started for this purpose. He was quickly recaptured and at some point moved into the Tower near the Earl of Warwick and then sharing his room, persuaded him to escape. The guards allowed this escape, giving the King the excuse he needed for this was the treason he needed to have the two young men executed. Henry was in two minds but in the end he had the guards tried for show, the Earl tried at Westminster as befitting his status and Warbeck at the Guildhall, without acknowledging his assumed status. In November 1499 Warwick was beheaded and Warbeck hung as a common felon.

Henry was known for his patience and his caution. His treatment of Edward of Warwick may seem callous, cruel, but it was now a necessity that the King believed he could no longer avoid. He had the security of a realm torn apart by suspicions and rebellion and his children to think of and there now appeared that this was the only way forward. Warwick most likely had little real knowledge of what was going on, but he was tried and condemned and as the Spanish Ambassador later wrote, Henry emptied England of “every last drop of doubtful royal blood” .