A big thank you to Amanda Glover for sharing with us her brand new, ground-breaking research into the "From the Lady in the Tower" letter said to have been written by Anne Boleyn in May 1536 when she was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Please do read through Amanda's findings and share your thoughts.

Over to Amanda...

The Background

There can be few, if any, who have the remotest interest in Tudor history, who do not know the story of the bloody death of Anne Boleyn, executed by her husband Henry VIII on what is now almost universally accepted to have been completely trumped-up charges of adultery, incest and treason.

There is therefore little need for the purpose of this article to go into the background of the events which led to Anne’s arrest on the 2nd May 1536, and her execution by a swordsman at the Tower of London a mere 17 days thereafter.

Anne was not allowed to see her husband to put her case to him direct, but there is a possibility that she was permitted to write to him from the Tower.

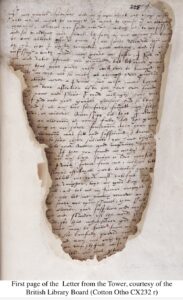

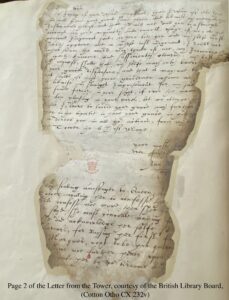

There is a letter, or rather a very large fragment of a letter, dated the 6th May (1536), which is now kept at the British Library, and which appears to be a letter from Anne to Henry.1

It comprises part of the Cotton Library, a large collection of manuscripts acquired by Sir Robert Bruce Cotton, (1571 to 1631), added to by his son and grandson, and ultimately left to the nation. It formed one of the three main founding collections of the British Museum.

The library, which contained many unique and priceless documents was severely damaged by fire on the 23rd October 1731, the Letter from the Tower being one of the casualties, although much of the letter remains intact. Fortunately, prior to the fire, copies had been made.

It is not known exactly when the letter was first discovered, but a copy of Anne’s letter exists which was made by an unidentified penman, (known only as the “Feathery Scribe”), who flourished between about 1625 and 1640. This document, also at the British Library, forms one of the Stowe Manuscripts.2 The British Library states that the volume in which the copy letter was found was collated in “about 1630.” This is only an approximation however, and the Library can only say with confidence that it was compiled in the 17th century. Nonetheless, it would be a fair guess to say that the Feathery Scribe produced his copy during his prolific period or within a few years either side. What is certain is that in 1649, the letter was published by Lord Herbert of Cherbury in a book on Henry VIII.3 If the letter is a forgery therefore, it was fabricated by 1649 at the latest.

The original is said to have been found among Thomas Cromwell's papers. Cromwell, Henry's chief minister had prepared the case against Anne, his known adversary, concocting the evidence from very few, if any, facts. Most documents destined for Henry would have passed through his hands.

The letter, if genuine, is a remarkable document. It seems to be in response to a demand by Henry that the queen confess her wrongdoing.

It is powerfully worded, professing Anne’s innocence and demanding a fair trial. It continues, that if Henry would only be happy by seeing her dead and terribly slandered, she hoped that God would pardon his “great sin” for his “unprincely and cruel usage” of her.

Sir your grace’s displeasure and my imprisonment are things so strange unto me, as what to write, or what to excuse, I am altogether ignorant. Whereas you send unto me (willing me to confess a truth and so to obtain your favour), by such a one, whom you know to be my ancient professed enemy; I no sooner received this message by him, than I rightly conceived your meaning; and if, as you say, confessing a truth indeed may procure my safety, I shall, with all willingness and duty, perform your command. But let not your grace ever imagine that your poor wife will ever be brought to acknowledge a fault, where not so much as a thought thereof ever proceeded. And to speak the truth, never a Prince had wife more loyal in all duty, and in all true affection, than you have ever found in Anne Boleyn, with which name and place I could willingly have contented myself if God and your grace’s pleasure had so been pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forget myself in my exaltation, or received queenship, but that I always looked for such an alteration as now I find; for the ground of my preferment being on no surer foundation than your grace’s fancy, the least alteration was fit and sufficient (I know) to draw that fancy to some other subject.

You have chosen me from a low estate to be your queen and companion, far beyond my desert or desire; If then you found me worthy of such honour, good your grace, let not any light fancy or bad counsel of mine enemies withdraw your princely favour from me, neither let that stain-that unworthy stain of disloyal heart towards your good grace, ever cast so foul a blot on your your most dutiful wife and the infant Princess your daughter.

Try me, good king, but let me have a lawful trial, and let not my sworn enemies sit as my accusers and as my judges: yea, let me receive an open trial, for my truth shall fear no open shames; then shall you see either mine innocency cleared, your suspicions and conscience satisfied, and ignominy and slander of the world stopped, or my guilt openly declared. So that whatsoever God or you may determine of me, your grace may be freed from an open censure and mine offence being so lawfully proved, your grace is at liberty, both before God and man, not only to execute worthy punishment on me, as an unfaithful wife, but to follow your affection already settled on that party, for whose sake I am now as I am; whose name I could some good while since, have pointed unto;-your grace being not ignorant of my suspicion therein.

But if you have already determined of me, and that not only my death, but an infamous slander, must bring you the joying of your desired happiness, then I desire of God that he will pardon your great sin herein, and, likewise, my enemies, the instruments thereof, and that he will not call you to a straight account for your unprincely and cruel usage of me at his general judgement-seat, where both you and myself must shortly appear; and in whose just judgement, I doubt not (whatsoever the world may think of me) my innocency shall be openly known and sufficiently cleared.

My last and only request shall be, that myself may only bear the burden of your grace’s displeasure, and that it may not touch the innocent souls of those poor gentlemen, who (as I understand) are likewise in strait imprisonment for my sake.

If ever I have found favour in your sight - if ever the name of Anne Boleyn have been pleasing in your ears - then let me obtain this request; and so I will leave to trouble your grace any further: with mine earnest prayer to the Trinity to have your grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your actions.

From my doleful prison in the Tower, the 6th of May.

Your most loyal and ever faithful wife.

ANN BOLEYN

Since the discovery of the letter, historians have debated its authenticity. Indeed, an entire book has been written about it.4 It is generally accepted that it is not in Anne's hand, but it has been suggested that she dictated it, either because she was too distraught to write clearly, or because she was not permitted to write herself. Even in these circumstances one would have expected Anne to have signed the document, but it does not bear her signature. Perhaps, it is argued, the letter is a contemporary copy, taken by Cromwell for his personal records.

Because of this, the debate has centred around the style of the letter - whether it was Anne’s type of language, whether she had written in a similar style before, or whether in such perilous circumstances she was likely to have written in such terms.

All these points are not only rather subjective, but also there is very little evidence of Anne’s correspondence to go on. Only a handful of letters written by her are known to exist, and they are essentially business letters.

By their very nature, they are highly likely to differ in style from a letter by the queen of England to her husband, while she was in such dire straits, and upon which her life may have depended. We can only speculate, and opinion remains divided.

Dr Andrea Clarke, an expert on early modern manuscripts at the British Library, has offered her opinion that the handwriting contains certain characteristics which are more of a late 16th century style than an earlier hand. Others disagree.5 The study of handwriting is not an exact science, and more concrete evidence is required to establish one way or the other whether the letter is genuine.

Sandra Vasoli, in the “genuine” camp, has attempted to establish the provenance of the letter, by providing a reasonable explanation as to how it became part of the Cotton Library, tracing its potential history back to Cromwell's papers.

Provenance is an important part of establishing the authenticity of any item. However even if it can be established that the letter could have passed to Cotton from Cromwell through various known associates over the generations, without corroborating evidence that it did (of which there is none), such evidence, at best, is only circumstantial.

Furthermore, it is known that the Cotton family purchased many important manuscripts and other documents from many sources.

It was therefore decided to adopt a completely new approach, and to look at the paper itself for clues as to its age, rather than investigating its contents, its style or its purported passage from the hands of Cromwell to its current home.

If the paper could be dated to around the time of Anne's death, then it is more likely to be a genuine original; if it was dated to sometime after her death then it could not be so.

The sacrifice of a fragment of the paper for the purpose of carbon dating would not be permitted, beside which carbon dating is too inaccurate for this particular research.

Early Modern Paper

Handmade paper has much to tell. Indeed, on occasions it can be almost as accurate as a fingerprint.

Such paper was made in the same way for hundreds of years. A rectangular wooden frame known as a mould, with a very fine mesh of wires like a sieve in one direction, and slightly thicker wires, spaced about 20 to 30mm or so apart, in the other was drawn through the top of a vat of pulp, (the stock), by a vat man. This caused a thin layer of the stock to lie on top of the mesh, forming the embryonic paper. The vatman allowed the mould to drain for a brief period and then he handed it to his colleague, the coucher, who carefully turned it over, dropping the newly formed saturated sheet onto a layer of felt to commence the drying process. Another layer of felt was added on top and a pile of felt alternating with paper was gradually built up in the process. This was then pressed to remove the excess water. When the pile had been sufficiently pressed, and the water drained, the individual sheets became firm enough to handle and they were hung up to dry.

The normal and most efficient way to create paper in this manner was to work with a pair of identical moulds, called twins. As one sheet of paper was forming in the first mould, the second was being turned out onto the felt.

In the 16th century most of the pulp was made from hemp and macerated linen rags which had been carefully sorted and treated in a variety of processes.

Each stage of the papermaking required a considerable skill, and the paper produced at each mill had its own characteristics. Even the way a particular vat man shook the mould or a coucher turned it onto the felt could influence the finished results.

The finished paper would retain a faint impression of the mould, including the wires, any imperfections and watermarks.

The best way of identifying or dating paper, is by examining the watermark and searching for the same mark in other paper of certain provenance, although some luck is required, because many watermarks have yet to be documented. If an identical, or near identical mark cannot be found, some information can still be gained from studying the trends in marks for a particular period.

Like all other processes in the making of paper, watermarks were made by hand, with fine wires being twisted into the shape of the chosen mark and stitched onto the wire mesh of the mould. Watermarks in the twin moulds were intended to be identical, but because they were handmade there were inevitable differences.

The moulds themselves did not last indefinitely. The constant drawing of the mould through the stock, and turning it out onto the felt, caused considerable wear. The mesh would gradually become damaged so that there was no longer a uniform grid upon which the thin layer of pulp could lie, and the twin moulds would then be discarded.

Similarly, constant use of the mould would often distort the watermark, although as that was not crucial to the quality of the paper, a distorted mark could still be used. A more severely damaged mark would have to be replaced.

Sometimes if a mould, or watermark broke, and had to be replaced, but its twin was still in good order, a new mould or mark would be made to match the remaining twin, creating a “triplet”.

It has been estimated that a mould of normal use was likely to have been replaced, together with its watermark, about every year or two, although moulds which were used less frequently, for example for unusual paper sizes, may have lasted up to about four years.

Some mills had more than one vat and they had one pair of moulds, (at least for the common sizes of paper) for each vat, all with essentially the same watermarks, with the inevitable slight differences as a result of being handmade.

As watermarks were renewed, they were altered. They tended to evolve, becoming more elaborate, or sometimes completely changing in appearance. No design lasted many years.

Hence by identifying a watermark, paper can be reasonably accurately dated.

The New Research

Anne’s Letter from the Tower is extremely fragile, due to the fire damage, as well as its age, and for this reason, access to it is restricted.

However, the British Library kindly gave consent for the document to be examined in a darkened room, with a light sheet beneath the page, in order to view the watermark as clearly as possible.

The letter is bound into a volume containing many other historic documents, which were also damaged by the fire, and therefore care had to be taken not to harm these as the light sheet was placed under the page.

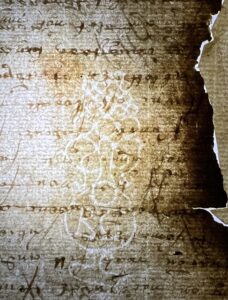

The examination revealed the watermark, which although shadowy, was sufficient to enable the search for a similar mark on paper of a known date to begin.

It showed an image of a double handled pot with what appeared to be a pile of grapes on top, three large ones on the bottom row and five smaller ones above that, topped with several more rows of small grapes. There were three characters in the body of the pot, one being above the other two. The top one was an O, or perhaps a circle. The two beneath, which were placed side by side, were an R, and a G. The foot of the pot was rather sausage shaped, on a small stem similar to that of a modern wine glass, and it was slightly tilted, possibly as a result of distortion during the use of the mould.

The dimensions of the pot were measured with an ordinary ruler as accurately as reasonably possible, bearing in mind the paper’s delicate state, and the fact that marking the paper was to be avoided. The exact position of the highest grape was a little obscured by the writing which also slightly impeded the measurement.

It was about 53 mm high from the lower end of the tilting foot, 19mm wide at its widest point, and about 17mm at the bowl.

There are a number of databases in which known watermarks have been registered. The Memory of Paper website provides access to 42 separate databases, containing over 254,000 watermarks. Every pot on this site, which was used in watermarks between 1460 and 1660, of which there were well over 2000, was investigated, together with another potentially relevant source -Piccard Online.

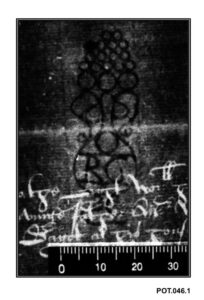

Two almost identical watermarks, very closely matching the one on the Letter from the Tower, were found in the Gravell Watermark archive, being POT.046.1 and POT. 242.1.

POT. 046.1 measures 52mm high and 13mm wide, POT. 242.1 being 58mm high and 18mm wide.

Save for the dimensions, there are only two minor discrepancies between all three marks.

The foot on POT. 242.1 is a different shape from the Tower foot, resembling the shape of a coat hanger, although the stem is the same, and it tilts in the same direction.

The foot of POT. 046.1 is somewhat obscured by the writing over it, (which appears in white in the image), and therefore it is not possible to be completely certain as to its exact shape. Nonetheless, it appears to be very similar to the foot on the Letter from the Tower.

Although it is difficult to see clearly in some of the images, all three marks have essentially the same pattern of grapes, with three large grapes on the bottom, being topped with a row of five, and then several rows piled in a pyramid shape, although the grapes in the Tower mark appear a little squashed, and there may be some missing at the top. Similarly, there may be a missing grape or two from the top of POT.046.1.

- Pot from the Gravell Watermark archive

- Pot from the Gravell Watermark archive

The three watermarks are therefore extremely similar, but not completely identical.

Peter Bower, a past handmade paper manufacturer, and now an expert forensic paper analyst and paper historian, based in London, was consulted.

He advised that for numerous reasons watermarks on handmade paper will not necessarily be identical in all sheets of paper made from the same mould.

There are many factors which can affect the measurements of watermarks. These include the drying conditions, such as the temperature and humidity, the number of sheets being dried together, and even the position in the mill upon which the sheets are hung up to dry, as well as the exact constitution of the stock, and the individual craftsmen working on the paper. Peter Bower stated that from his own experience his sheets would shrink slightly more in the vertical than those of his partner, which shrank slightly more in the horizontal direction. This would affect the size of the watermark itself. He has found a difference in the size of watermarks on paper made from the exact same mould to be as much as 6.35 mm, in both directions.

The variation in the measurements between the three marks in this instance, is therefore within the possible range of variation in sheets made from the same mould for the above reasons alone.

Other discrepancies, such as in the grapes could well be as a result of damage, and that too can affect the measurements. The grapes would have been very delicate, and some could easily have been injured, distorted or destroyed, by accident or simply by the repeated use of the mould, resulting in the loss of their pyramid shape and a reduction in their height.

Minor damage may not have been repaired at all, or may have been casually repaired, altering the appearance of the watermark on the paper. Furthermore, the wires creating the watermarks could move and distort slightly, being relatively loosely stitched onto the mould.

Possibly the original foot was of the coat hanger design but a pull in the centre rendered it more sausage shaped. The converse could also be the case. A knock to the middle of the foot of POT.242.1 could have resulted in its outline becoming more of a coat hanger shape than the sausage shape of the Tower mark, or maybe the difference is as a result of a casual repair.

Taking all the facts into account it was concluded that the three pieces of paper upon which the three watermarks appear are likely to have been made from the same mould, a twin mould, or possibly a triplet. If they were not, they were made by the same mill within a relatively short time of each other.

They are far too alike to have been made in a different mill, or to have been produced more than a very few years apart at most.

Both the examples found on the database are situated at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC, USA, and they were derived from the same collection- the Bagot papers. Walter Bagot was the recipient of both letters, one being written by his son Harvey, and the other by a kinsman by marriage, Anthony Kynnersley.

The crucial information is of course the date of these letters. Harvey Bagot wrote to his father, (using paper with watermark POT.046.1), on May 17th 1609, and Anthony Kynnersley wrote his letter, (with watermark POT.242.1), on 23rd March 1606.6

If the letter at the Cotton Library was a letter dictated by Anne, or a copy of such letter taken by Cromwell, the paper would have to have been manufactured, and delivered to its user by the 6th May 1536, or within a few days of this in the case of Cromwell’s copy, 70 years before Anthony Kynnersley picked up his quill to write to Walter Bagot.

Kynnersley would not have used 70-year-old paper. The fact that Harvey Bagot was writing with paper made from the same, or near identical mould three years later confirms that the paper was most likely to have been produced no earlier than the first few years of the 17th century.

Although paper merchants and their customers may each have stored their paper for a time, it is highly unlikely that the two combined periods would have been more than four or five years at most.

Furthermore, no watermarks, even vaguely resembling the marks in question could be found any earlier than the very late 16th century.

Although pots were found throughout the 16th century, the earlier ones tended to be in a much simpler form. Letters in the body of the pot were unusual, appearing a little towards the middle of the century, and becoming much more frequent at the end. There were a handful found dating from 1539, still three years after Anne’s death, but all from a Lisbon mill, and their style was very different. Most paper during this era was imported to England from the Normandy area or the Pas de Calais, where pots in watermarks were common, and it is probable that this is the origin of the paper upon which the Letter from the Tower was written. A watermark similar to, but not identical to the mark on the Letter from the Tower, bearing letters in a two handled pot topped with grapes, together with the date 1598 was produced by the Normandy paper maker I. Ganne.7

Although very simplified flowers sometimes appeared as embellishments on top of pots early in the 16th century, (in particular in the German states),8 there was nothing resembling grapes, and the early marks were consistently of a more basic design.

By the end of the century however, pots had frequently evolved into more elaborate styles often containing letters in the body, more complex handles, and intricate motifs on top, much as the watermark in the Letter from the Tower.

The first motifs resembling grapes that could be found topping a pot appeared in the last decade of the 16th century.9 Numerous examples were found in the first decade of the 17th century, but they had more or less died out by the end of the decade. A single example was found on paper used in 1619.10 Grapes did start reappearing in the middle of the seventeenth century but combined with a crescent, and the pots were of a somewhat different style.11

Conclusion

We must therefore conclude with very little doubt that the paper upon which Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower was written, and which now forms part of the Cotton Library, was manufactured in the first decade of the 17th century. It cannot be an original of a letter dictated by Anne, or a copy made for Thomas Cromwell.

If it was found among Cromwell's papers, some unknown person must have slipped in the letter 60 years or so after Cromwell himself had followed Anne to the scaffold.

At best, the letter is a copy of a lost original, made many decades after Anne’s death, in which case we must ask ourselves who made such a copy, where the original had been kept unnoticed for all those years and why it then disappeared? At worst it is simply a forgery, which begs the questions by whom and to what end?

Further thoughts and observations

This article has concentrated on the research as to the age of the paper. However, during the course of investigation, the writer has come across various discrepancies or facts worthy of consideration. Unfortunately, much research has been curtailed because since a major cyber-attack at the British Library in late October 2023 remote access to the library and even physical access to many manuscripts has not been possible. Much further research and consideration is needed but some of the points are briefly summarised below.

- By far the most common reason for forgery is for financial, or at least some form of personal gain. It could therefore be concluded that the Cotton family purchased the letter which is now in the Cotton Library from the forger himself when it was actually written i.e. about 1605 to 1610 if it were not for the following fact:-

Bishop Burnet published the History of the Reformation of the Church of England in 1679.In part I book III page 332, he states with reference to the letter:-

“Yet the copy I take it from, lying among Cromwell's other papers, makes me believe it was truly written by her”.He is saying that he himself had seen the letter amongst Cromwell’s papers, and that he had made his own copy from that letter. As he was not born until 1643, he must have seen it several decades after the supposed forger wrote it. Therefore, assuming Burnet is correctly reporting the facts, the Cotton family could not have purchased the document from the forger, if indeed it is a forgery.

Did the forger therefore merely quietly place the letter among Cromwell’s papers somehow, in the first decade of the 17th century, but make no mention of it and derive no gain from it? Did he just wait patiently for some historian to find the letter decades later, possibly even after his death? Is it likely that a forger would have done this?

- In the Feathery Scribe’s version of the letter (i.e. that in the Stowe Manuscripts), there is the following heading:-

“Queen Anne Bulling

For king Henry the 8 ffounde amongst

Cromwell’s papers”.This heading does not appear in the Cotton Library version. Such a heading could not have been lost in the fire, as the top of the letter, where the heading would have appeared, has suffered very little from the flames.

If the Feathery Scribe was copying the Cotton Library letter, as has been generally presumed, why would he add such a heading? Was he in fact copying, not the Cotton Library letter, but an original (now lost), which he did actually see amongst Cromwell’s papers? Alternatively, was the Feathery Scribe copying what is now the Cotton Library letter but which at the time was still amongst Cromwell's papers, not yet having been acquired by the Cotton family? In both such scenarios the heading would have been appropriate. In the second scenario however, the Feathery Scribe could have been copying a forgery, (or perhaps a copy of an original, but what was such a late copy doing amongst Cromwell’s papers?), and the Cotton family cannot have acquired the document until after Bishop Burnett had also seen the letter amongst Cromwell's papers.

- The Cotton Library letter contains a note at the end, after the position for the signature, of a conversation which is said to have taken place in which Anne stated that the king had raised her first from an ordinary woman to be a Marquis, next to be his queen, and now seeing that he could bestow no further honour upon her on earth, he was, by martyrdom making her a saint in heaven. It does not specify the date upon which the conversation is said to have taken place.

It is true to say that this part of the document is badly burned, and it is conceivable that a date may have originally appeared, but from what remains it does not initially appear to the writer that the burnt part would have been the obvious place for the date to have been written. Furthermore, it would seem that a copy taken before the fire does not include a date.

Bishop Burnet makes no reference to the fact that this note was to be found at the end of the letter, but he does relate the story, (at page 329). He also states that the conversation took place on the day before Anne was executed – i.e. on 18th May 1536.

If Bishop Burnet had merely discovered the Cotton Library version of the letter, from where did he find the date and why did he not link the letter and the note in his book?

Could this be because the version he found amongst Cromwell’s papers was an original letter dictated by Anne, or maybe Cromwell’s copy, without the addition of the anecdote, and that he found a separate note of the anecdote which referred to the date?

It is of course possible that Cromwell's own copy, if it ever existed did have a note of the anecdote added to it, for his records, and that Burnet merely chose not to mention this. It may also have mentioned the date. Burnet did not find the date in the Cotton version.

The Feathery Scribe’s version does not include the anecdote. Is this because he was indeed copying an original which did not have the anecdote annexed, or simply because he was for some reason instructed only to copy the letter forged or otherwise, rather than the entire document?

- Is it therefore possible or even probable that both the Cotton and the Stowe letters are themselves copies independently made from either an original letter written or dictated by Anne, or a copy taken by Cromwell for his records, which was indeed originally found amongst Cromwell’s papers, but which has now been lost?

Of course, Cotton and Stowe could both be copies of a forgery in which case two parties were independently duped, and how Burnet determined the date for the forged anecdote remains unknown!

- This brings us to the question as to whether it is likely that the Cottons would have been easily fooled.

From the moment Sir Robert Bruce Cotton started collecting documents, his library became a trusted source of information, presumably for good reason. It was regularly used by academics, MPs etc, who sometimes relied upon it when conducting important business.

According to the 1702 Act of Parliament which was passed to deal with the care of the Cotton Library when it was given to the nation, the family had employed the most learned antiquaries of the time when amassing their collection.

Would the most learned antiquaries have been duped? Would they have accepted the letter as being genuine purely because it was found amongst Cromwell’s papers? Possibly – Burnet seems to have done so, but would the most learned antiquaries not have required a little more concrete evidence? We do not know.

©Amanda Glover 2024

Acknowledgements

With grateful thanks to the following:-

Claire Ridgway, historian and expert on Anne Boleyn, for her encouragement and assistance in researching watermarks; The British Library, and in particular Dr Andrea Clarke; Peter Bower, and Heather Wolfe of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Notes and Sources

- British Library Otho C X f232 r&v.

- British Library Stowe 151.

- The Life and Raigne of King Henry the Eighth. p. 382.

- Sandra Vasoli. Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower.

- Sandra Vasoli. Anne Boleyn’s Letter from the Tower, 2023 edition, pp. 45 and 46.

- Written as 23rd March 1605 as until 1752 the legal new year commenced on 25th March rather than 1st January.

- Gravell Watermark Archive Pot.011.1 Used in 1604.

- E.g. Piccard Watermark Collection J.340. No. 31132 dated 1505 from Koln (Cologne).

- E.g. pot.066.1 Gravell database. 1594.

- Gravell database pot 195.1.

- E.g. Gravell database pot 421.1.

I have read and reread the letter on multiple occasions. The tone of it unsettles me, as it is very accusatory for someone knowing her life was in peril. I cannot imagine if Henry read it that he would have been sympathetic, but rather, defensive. I wonder therefore if she wrote her feelings down impetuously but never sent it and it was found and given to Cromwell after her execution. If she had sent a letter to Henry I think it would have been more loving, to appeal to his emotional nature. I don’t think the existing one would have worked in her favour. Therefore my conclusion is that certainly it may be a copy of a copy of a letter Ann Boleyn wrote impulsively in the Tower but I think she was too intelligent to actually send one so likely to have incurred indignation by its recipient.

Excellent research! I greatly enjoyed reading this.

Like the previous commenter, I had always looked askance at the language Anne uses in this letter. I mean, it’s what she SHOULD have said to Henry, but it seems unlikely a woman pleading for her life would be so blunt as to say she was in the Tower just because Henry preferred another. She also says her crown rested only on Henry’s fancy, which is odd considering she’d been crowned and anointed – something “all the water of the rough, rude sea cannot wash away.” Lastly, that she signed the letter “Anne Bullen” [Boleyn] instead of her title, Anne the Quene. Wouldn’t she have wanted to stress the legitimacy of her title as his wife, and not a name she hadn’t used since 1525?

Wow! Thank you for doing such an excellent deep dive on this fascinating piece of history. Watermarks. Genius! The age of the paper certainly clarifies some things, but this is such a mystery still.

This document is and always will be a mystery, once I was firmly of the opinion that it is a copy as the comments above state, why did Anne not sign her name as queen it was her correct title? Why was it not headed above as written by the queen, but the lady in the tower, that to me smacks of a Victorian style novel, but there are arguments for as well as against, it is a passionate articulate letter and although some may argue the style is 16th c I believe it is the sort of letter she would write to her husband the king, in it she explains how baffling she finds her incarceration and she pleads with him to let her have a fair trial, she reminds him of the great affection he once held her in and mentions their daughter the princess Elizabeth, her alleged lovers to get a mention she pleads for their innocence and this is very telling, she mentioned them at their trial, yet she did dare mention the fact that she is in the tower for other reasons and would she have dared? She had to tread very very carefully yet Anne had always possessed great courage some one said once of her she was as brave as a lion, however then she had still been the object of Henry V111’s desire and now she was a prisoner in the Tower, the first few days she gave way to hysterics and I don’t believe she was calm enough to write such a letter or even dictate one, she laughed she cried and babbled incessantly, would also she have been allowed writing materials? Sandra Vasoli whose book I have yet to read believes it is authentic, I will have to buy a copy and determine for myself, as yet I cannot make up my mind about it but how wonderful if it was authenticated as written by Anne, what a rare treasure it would be as there are only a few letters written by her that survive, the research about the watermarks is wonderful, I agree Claire you always do great research.

Great article! FWIW, I don’t believe that Anne wrote the letter. She knew that Henry had no qualms about mis-treating his kids (Mary) when he got mad at mom. She would not have endangered Elizabeth by telling Henry what he was doing and that it was wrong.

This is true because when a prisoner was in fear of their life the last thing they wanted to do was wind up the king, his temper was notorious and Henry V111 was not known for his mercy, hence why scaffold speeches always praised the sovereign they wished no retribution on the loved ones they were leaving behind .

Could the spelling be this accurate for a letter written in 1536? Even if a scribe had particularly good spelling the letter appears to me to be far to correct to be from this period.